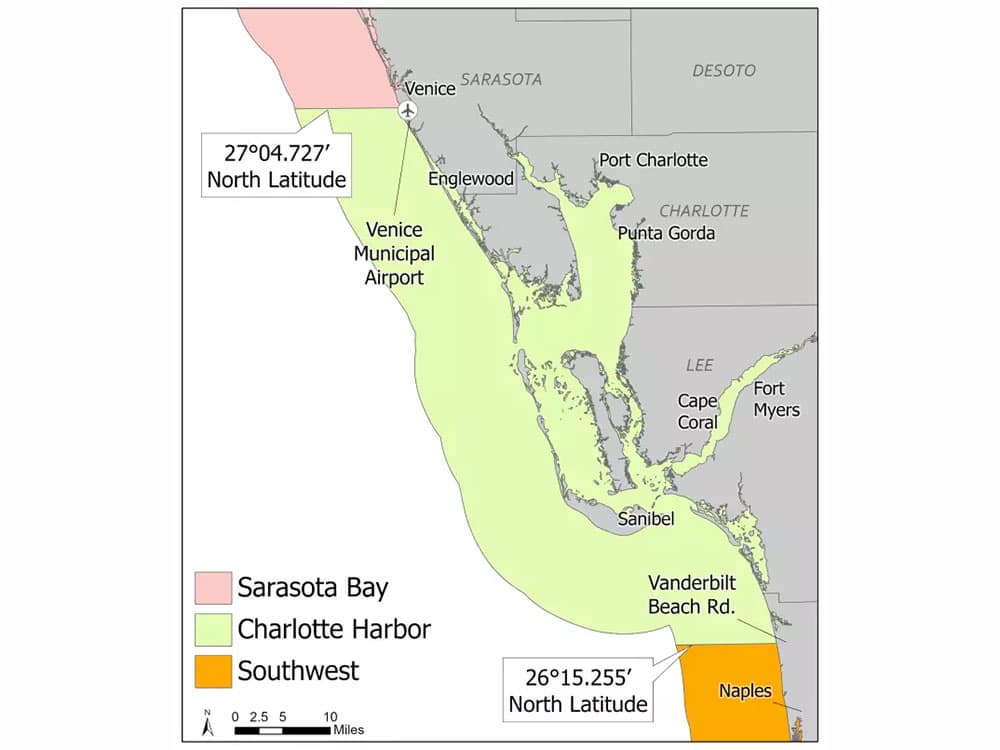

In the sometimes confusing and changing world of Florida gamefish regulations, anglers need to pay attention to updates to stay legal. Due to an executive order issued by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) on September 1, anglers in the Charlotte Harbor region (all state waters south of a point near the Venice Municipal Airport extending south to Vanderbilt Beach Road in Collier County) must release their snook until March 1, 2023. This includes all waters of the Peace and Myakka rivers as well.

This no-kill extension gives snook stocks a bit more protection, something FWC fisheries managers and many anglers and guides feel is needed. FWC cites ongoing seagrass habitat loss (exacerbated by repeated, chronic red tide events) as reason enough to issue this executive order.

Emily Abellera, Public Information Specialist for FWC’s Division of Marine Fisheries Management, makes clear that habitat loss has a cascading effect on the forage species that support not only snook, but popular fish such as red drum and spotted seatrout in Charlotte Harbor waters. When asked whether FWC was factoring in the likely effects of Hurricane Ian’s winds and copious rainfall, causing polluted runoff into Harbor waters, Abellera said that will be addressed eventually.

“At present all of our resources in the field are involved in initial hurricane recovery, including resident safety and more,” said Abellera. “Ian’s impacts on an already impaired seagrass community and the snook that depend on it will certainly be assessed.”

Gulf Coast Snook Harvest on Hold

Capt. Greg Stamper, of Snook Stamp Charters, guides clients throughout Charlotte Harbor from Bonita Springs to the Caloosahatchee River. He enthusiastically supports the extended closure.

“I think the additional closure is great,” said Stamper. “I’m a catch-and-release guide when it comes to snook, even when it is open harvest season. I haven’t killed one in 15-plus years. The devastating impacts of red tide, poor water management, over-development, angling pressure and seagrass loss justifies tightening the regulations to protect the stocks.” Stamper has a no-kill snook policy on all of his charters.

In Bonita Beach, Master Bait & Tackle shop owner Todd Dutro is fully in favor of the extended protection for snook. However, he and many customers fish Estero Bay, where seagrass is not prevalent.

“I’m very happy to see the FWC’s proactive measure on snook,” said Dutro. “I’ll put in this way, if you keep telling people you can’t have a red truck, they will do anything to get that red truck. In other words, customers who have dealt with long snook closures on the Gulf coast ask me, ‘When can I kill a snook?’

“It’s to the point that I fear that when things do open up again, the efforts to harvest snook will increase. Consider the thousands of anglers and many hundreds of guides after them, and I believe over-harvesting is a real possibility.”

Loss of Habitat Destroys Snook Populations

The region has been hammered repeatedly by chronic red tide in the last decade, most recently in 2018 and 2021. More than 790 tons of dead fish and marine life, perished along much of the West Central and Southwest coast in the last event. Many breeding size snook were in the mix. Marine biologists are increasingly suspect of the dense Cyanobacteria blooms (called blue-green algae) coming from Lake Okeechobee and the local Caloosahatchee River tidal basin discharges. Some feel the bloom and nutrient-rich runoff feeds the red tide, also a harmful algal bloom. Charlotte Harbor seagrass are sunlight-starved, and stressed by too much fresh water during these discharge events, causing widespread mortality.