skagit casting

Of all the casting columns I’ve written, this one is the first in which I feel obliged to confront the issue of a justifying rationale. Even when I mentioned the mere prospect of writing such a piece to some of my dyed-in-the-salt fly-fishing buddies, I was greeted with comments like, “Why would you write that? There is no application for saltwater fishing.” Like most dogmatic pronouncements, that’s not entirely true, but to properly address the argument, let’s recognize that the word application in the sense it is being used here refers as much to personal inclination as practicality. In terms of the latter meaning, I would argue that there are definitely applications for spey-casting in saltwater environments.

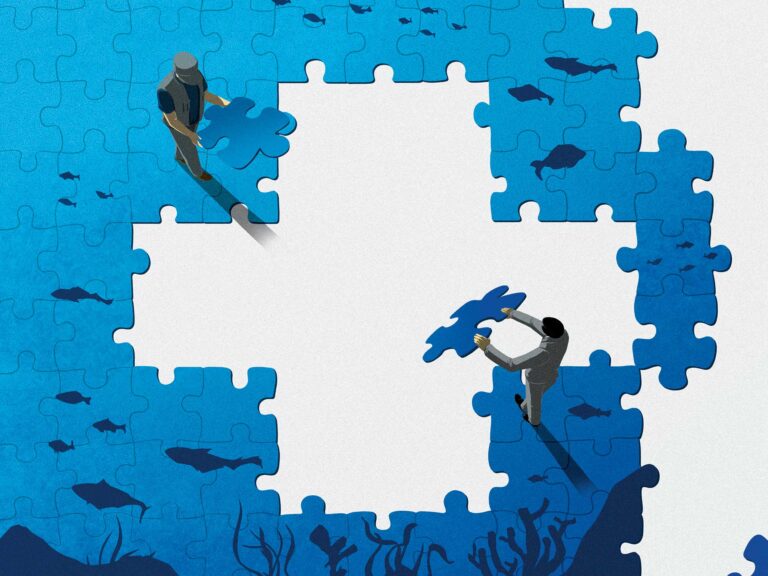

Visual Appeal

Even with today’s advances in spey line design, effectively casting with 70 feet or more outside the rod tip requires a great deal of practice. Living as close to San Francisco’s Golden Gate casting ponds as I presently do afforded me the opportunity to learn these casts. However, I want to quickly add that for most of the actual fishing I do, I will probably never use these lines. I wanted to learn simply because I found these casts so visually compelling. They look great! And when you execute these casts correctly, they feel great! I’ve derived a great deal of satisfaction from the challenge they have provided. A friend who does a lot of steelhead fishing echoed this sentiment when he stated, “You have to make so many casts for these fish, you might as well have fun while you’re doing it.”

Of course, you are free to fish any way you like — but I was taken aback when a guy who was watching me cast such a line some time ago commented that he would like to try this while wading for permit. I stopped casting immediately and tried to enlighten him about how this would not be a very effective way to go. Even with the so-called touch-and-go casts, the line striking the water creates noise and some degree of surface disturbance, two factors you want to avoid when fishing shallow flats. Normally in shallow-water situations, stealth is the order of the day, and it takes on paramount importance when you set your sights on something as wary as permit. Another disadvantage in these circumstances is that it is difficult to execute pinpoint presentations when making a spey-type cast with a two-handed rod. Accuracy is a very important part of the game when you’re sight-fishing skinny water, and a single-handed cast makes the job a lot easier. These limitations notwithstanding, I’m sure the feat could be pulled off successfully, and it’s your choice whether you want to endure these added handicaps. My personal take is that despite the fact that I derive a great deal of enjoyment executing presentations with double-handed casts, I’m not willing to unduly compromise my fly-fishing efforts.

When to Use

Since most of the rods used for this type of casting are at least 11 feet in length, I wouldn’t recommend them for fishing from a boat. The added length compromises their fish-fighting ability (the longer section of the lever is on the fish’s side of the balance) and makes the landing process that much more difficult. Maneuvering a fish close to the boat in preparation for release can be an unwieldy task even with rods in the 9-foot class. If you are trying to do this by yourself, the longer rod will prove a significant hindrance. And as far as distance is concerned, dangerous locales aside, the fact that you’re in a boat should minimize the need for hero casts.

There are, however, two spey-type lines that do have ready application for salt water. These are the shorter-belly lines marketed as Scandinavian shooting heads and the more recently developed Skagit heads. Both have head sections that can range from 19 to about 27 feet. The rods used with these lines are also shorter than traditional spey rods and generally range from 11 to 14 feet. Due primarily to the lines’ shorter belly sections, learning to cast them is a great deal easier than what you’ll experience with a long-belly spey line. With Skagit lines, the belly section floats, but you can fish a variety of depths with the addition of 10- to 15-foot tip sections in varying densities, from full floating to extra-fast sinking. The first time you spool one of these lines on your reel, you may be surprised at the relatively large diameter of the belly section. But this added girth is needed to turn over heavy sink tips and large weighted flies.

The casts executed with these lines are all waterborne. This means that the cast is initiated with the belly section lying on the surface. The surface tension on the line bends the rod as the fly and leader are positioned for delivery to the target area. In addition to these lines’ relative casting ease and ability to handle heavy sink tips and large wind-resistant flies, an advantage over the traditional long-belly lines is that they require much less space to make a backcast. So if you find yourself having to fish an area where the room for a backcast is greatly restricted, these lines can prove a decided advantage.

Because I find them such fun to cast, I often use them in conjunction with two-handed rods in situations in which I’ve traditionally fished only with 9-foot single-handed sticks. One example is when I wade a tidal flat off a protected stretch of beachfront. In an area like this, it’s not a question of restricted space since there’s plenty of room for a standard backcast. But, particularly in those areas where there are drop-offs and troughs, longer double-handle rods with Skagit lines and fast sink tips are an effective way to get a fly into productive zones. Having fished these waters with both traditional single-handed rods with shooting heads and two-handed Skagit systems, I don’t feel one setup is more effective than the other. In situations like these, use the system you enjoy the most.

As with any activity of this sort, you will save yourself a great deal of time and effort if you begin the learning proc-ess with a competent instructor. Also important is to learn and practice on the water. It’s true that with specially tied leader setups, it’s possible to simulate the resistance of water tension, but it is nowhere near as realistic. These are waterborne casts, and water is what you need to practice on.