You know how it is when you go fishing: Sometimes the anticipation is even better than the real thing. Our anticipation level was hovering right up there among the ever-present bald eagles when we left Prince Rupert, British Columbia, for the two-hour boat trip to Wilp Syoon Wilderness Lodge and a weeklong bout with several species of Pacific salmon.

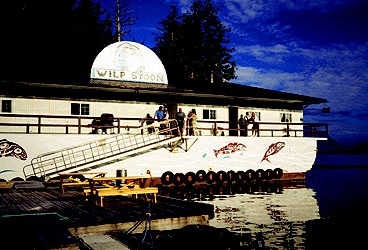

The boat’s skipper, a local veteran, stoked our enthusiasm with a wellspring of information about the area’s history and geography. His tales seemed to shorten the travel time, and almost before we knew it we had left Chatham Sound and were turning into a major east-west waterway (locally called an arm). Then we entered a second, smaller waterway, and suddenly Wilp Syoon Lodge was right before our eyes, tucked into a tiny protected bay.

Lodge manager Ken Bejcar, chief guide Josh Temple and other members of the lodge staff greeted my wife, Elizabeth, and me. Temple steered us through a quick tour of the lodge before we chose a room, changed into fishing clothes and rejoined our hosts in the dining room, where a buffet lunch was waiting. But Temple was more interested in fishing than eating; he told us to grab some food and a can of soda and head for the boat. He also told us to forget about rigging our own tackle – we could do that later. He had everything we’d need.

I have to admit, I don’t like using “lodge tackle” because it’s often inferior stuff in poor repair. Not so at Wilp Syoon; Temple and his crew have assembled appropriate Scott rod/

Ross reel combinations with a wide choice of lines and terminal tackle. Several guides also are competent fly tiers who experiment continually with new patterns to meet changing conditions.

The 10- or 15-minute run back to the main east-west arm gave us time to swallow our sandwiches and familiarize ourselves with the boat. Wilp Syoon hadn’t cut any corners here either: The boat was a nearly new 21-foot Boston Whaler powered by a 200-hp Mercury outboard with a 9.9-horse trolling motor and a full complement of electronics and safety equipment. The lodge also has a 26-foot Whaler with a pair of 200 Mercs for open ocean fishing, although we found during our week’s stay that the 21-footers were safe, comfortable ocean platforms as well.

That first afternoon brought us a single pink (humpback) salmon and one silver (coho), and we saw more salmon rolling on the surface, more eagles hovering overhead and surrounding scenery that was absolutely gorgeous. Obviously, this was no 9-to-5 fishing lodge. We would learn very quickly that it was more like a dawn-to-dusk operation if you wanted it that way – and we did.

Glacial House

From the native Nisgaa language, Wilp Syoon translates into English roughly as “Snow Hut.” The original native concept of the place apparently was actually something like “iceberg house,” but since the language has no word for that, Glacial House was the compromise. Whatever the name, the lodge represents an important precedent: It’s British Columbia’s first wholly native-owned facility of its kind.

Unlike the United States, Canada never signed treaties with its native peoples. European colonists simply moved in and took over instead. The Nisgaa, also known as the People of the Nass (for one of two major river systems emptying into Chatham Sound), decided to work with the interlopers rather than attack the wagon train. For nearly 100 years, representatives of the People of the Nass attended sessions of parliament in Ottawa and the British Columbia Legislative Assembly in Victoria, petitioning for parity with other Canadian citizens and the return of their lands. Finally, in 1998, both national and provincial governments agreed. In anticipation of eventual success, the Nisgaa by then were already well into planning for their own self-sufficiency. Wilp Syoon Wilderness Lodge was an early first step.

It’s also part of a larger strategy. Nisgaa lands and waters are rich in timber, minerals and fish, yet the people have chosen to avoid economic shortcuts in order to establish a long-term sustainable economy. Commercial fishing has been limited in favor of the economic benefits of sport fishing and ecotourism. Besides Wilp Syoon, future plans include a second saltwater lodge, a steelhead camp and a high-lake trout-fishing program.

White Water

Day two brought us slow fishing on the fly. It was early August, and the majority of the king (chinook) salmon already had made their way up the nearby rivers; the stragglers stayed low in the water column. Even with 500-grain shooting heads and large Clousers, it was hard to reach them, and even when we did our offers generally were greeted with indifference. Silver salmon were somewhat more accommodating, but they also stayed deep.

On the third day Temple took us to a new location. En route, while we were enjoying the crisp air and spectacular scenery, Temple said he’d heard that Elizabeth and I had been known to run white water in our McKenzie riverboat. Our acknowledgement brought a smile to his face and the promise that we were about to see some serious rapids.

As we passed a picturesque old abandoned salmon cannery, Temple suddenly rolled the boat on its port beam and headed straight for shore. Just as we were thinking about abandoning ship, a narrow channel appeared in the shoreline. It looked like a river of white water flowing into the main arm, but it turned out to be the constricted mouth of yet another tidal arm – this one 10 miles long and hard on the Alaska border. Whirlpools and pressure waves bounced and battered the speeding boat, but Temple quickly powered us through into a wonderland of steep cliffs and hanging waterfalls.

The hidden arm ended in a small delta where a pair of streams flowed out of a valley that reminded me of Yosemite. It looked like a place that just had to be stiff with salmon – and it was! Acres of pink salmon and a few early coho were milling around, waiting for the final urge to head upriver. When the light was right, it was possible to pick out the newest arrivals by their bright silver-gray coloration. We targeted these with 7- and 8-weight floating lines and small chartreuse Clousers, and were rarely refused.

All too soon Temple said it was time to go. We had entered the arm on a rising tide, which made running the rapids fairly easy, but now the tide was well into its ebb and falling rapidly. Tides within the narrow arm can vary by as much as 18 feet, and Temple said that when the water falls below a certain level it exposes rocks at the mouth of the arm, making the boat transit dangerous. At low tide the mouth is impossible to navigate, a fact he learned the hard way once when he had to wait 10 hours for high water to return.

Rockfish Salvation

The next day’s forecast of fog followed by sunny skies and a calm sea prompted Temple to suggest an ocean trip some 30 miles out to a group of small islands, where we’d have a chance to view abundant sea life and maybe catch a halibut or late-migrating chinook. So morning found us pushing westward through thick fog over green Pacific swells.

We ran 90 minutes before the fog finally showed signs of lifting and we spied a small island. Soon we were idling through floating kelp beds near the island, looking for rolling salmon. Finding none, we started blind-casting in tidal rips or likely spots along the shoreline. Eagles and ospreys soared overhead, seabirds were everywhere and a pair of whales wallowed in the kelp paddies like contented hippos – altogether a splendid show.

But the salmon didn’t show, so Temple suggested changing tackle and trying for rockfish, a suggestion we greeted with enthusiasm. Many species of rockfish frequent the Pacific from Northern California to Alaska, but they are mostly overlooked as fly-fishing targets. That’s odd, especially considering that one species, the black rockfish, tends to prowl the upper reaches of the water column and has a happy propensity to grab nearly any kind of fly it happens to see.

For us the fly was the same small chartreuse Clouser, fished on a short intermediate sinking head matched to an 8-weight rod. We cast into the kelp, let the fly sink 10 or 20 seconds and only rarely had to retrieve very far before there was an answering pull. In calm water we could even see the fish take. They ran 3 to 7 pounds, and each one put up a strong subsurface battle.

After two hours of battling blacks, we were sated, so Temple took us on a tour of the islands, pointing out rips and points where earlier he had found feeding chinook and coho. They weren’t there today, but we had no cause for regret; we’d already had a super day.

Ever the eager guide, Temple said he knew a spot on the way back where we might find a silver salmon or two. That’s nice, we said, but after 10 hours on the water, a hot shower and a cold libation sounded better. Of course we stopped anyway, and true to Temple’s prediction we caught a couple of nice coho and still made it back to the lodge before the cocktail flag was lowered. You’ve got to love those long Northern evenings.

We had scarcely commenced our assault on the chef’s tempting hors d’ouvres when we heard shouts from the dock, where the two young sons of another pair of lodge guests had been fishing for halibut. The boys had been told it was possible to catch these fish from the dock, and while everyone else dismissed it as “guide talk,” they had taken it seriously, spending every spare moment tending a rod the guides had set up for them.

Just now the rod was seriously bent, and the two boys were struggling to hold on. Their shouts brought everyone running, and we watched and offered all sorts of free advice while they fought to hold on to whatever was on the other end. At length a guide wielded his gaff and hoisted an 82-pound halibut onto the dock, where its proud conquerors posed for photos. It was a happy camp that night.

Sight-seeing

We’d told Temple we wanted to see more of the Nass country, so early the next morning we set some crab pots in the main arm and then headed for the place where the Nass river enters salt water. The water faded from crystal clear to cloudy as we neared the spot, finally becoming so thick with silt it looked as if it could be sliced with a blade – the result of summer glacial melt in the river’s Coastal Range headwaters. Our destination was one of four main villages of The People of the Nass, a tidy little port that also is the terminus of the main road that crosses their lands and serves as a link to the outside world. The scenery along this road is described as truly spectacular.

On the way back to fetch the crab pots, we stopped to fish a patch of clear water along the shoreline of a point. A chinook salmon hit my fly and ran briefly before coming unpinned; Temple saw it and said it was huge. Probably more “guide talk,” but it provided a momentary thrill for sure. Our luck with the crab pots was better, and we headed home with a good haul of the tasty critters.

That evening we spent some time talking with lodge manager Bejcar, Temple and some of the other guides and employees. All expressed enthusiasm for the lodge’s emphasis on catch-and-release fishing with a fly rod or on light tackle. Each seemed keenly aware that the fishing resource is finite and must be protected if it is to be sustained. The People of the Nass are proud of the efforts of their fishery managers to limit commercial fishing, monitor spawning escapement and repair the damage from past ill-advised land management practices. Their attitudes left us deeply impressed.

Next morning, our last at Wilp Syoon, some of our fellow guests opted for an early breakfast and a couple of hours with the salmon. We chose instead to bask in sunshine on the dock and enjoy a second cup of coffee and a cinnamon roll while we waited for the water taxi. In another couple of hours we were part of the happy weekend throng at the Prince Rupert Airport, weighted down by a cooler full of fresh crabmeat and a whole treasure chest of precious new memories.