| [1] A striped marlin often shows both the upper portion of its dorsal fin and the tip of its caudal fin when the fish is tailing or feeding, but the dorsal fin is usually angled steeply back, or folded completely, when the fish is “sleeping.” [2] As the sunfish, or mola mola swims at low speed, the semi-flaccid tip can droop and flap slightly from side to side. [3] The dolphin or porpoise exposes most of its dorsal fin above water as it slowly curves its body above the surface. The dorsal usually shows more curvature than those of sharks or marlin. [4] manta rays often cruise slowly on the surface. Sometimes, in this mode, mantas will curl and raise a smooth, rounded wingtip above the surface. [5] Most sharks have a softer, more rounded lobe-tip at the top of their dorsal fin, with usually about one-third of it exposed. [6] A seal or sea lion often rests or suns itself by lying on one side and floating, displaying one of its pectoral flippers for view, often waving it in the air. [7] A broadbill swordfish on the surface will expose half to three-quarters of a pointed dorsal fin with a scythe-like curve and broad base. Illustrations: Steve Sanford |

If there was a Pacific Marlin Fishing Hall of Fame, its corridors would surely echo the names of Pete Grosbeck, Gary Graham, Gary Jasper and Mark Wisch. Over the years I’ve enjoyed fishing with, interviewing or attending seminars conducted by these tournament pros and others men who have mastered everything from reading current breaks to understanding the roles of prop noise and stern turbulence on marlin behavior. Here’s what I’ve learned from these experts and others on one vital aspect of striped marlin angling hunting and baiting fish on the surface.

DON’T BE FOOLED BY FINS

Learn to recognize the surface-protruding shapes and characteristics of fins of various sea creatures. There are subtle, yet very important differences (see illustration).

A marlin, for instance, will often have portions of both its dorsal fin and tail fin showing; not so with most other finners. Know that the pectoral or side flipper of a sunning seal slowly flaps up and down, while the broad, dorsal tip of a lazing sunfish (mola mola) appears droopy. A shark’s more rounded dorsal is usually only about one-third exposed, except when aggressively feeding; the dorsal of a swordfish is scythe-shaped and pointy, compared to a marlin’s.

If you can’t distinguish the fins of a stripie from a sunfish or a shark, you’re going to waste a lot of time, effort and fuel investigating non-targets.

BE A BIRDWATCHER

|Greyhounding striped marlin provide a thrilling fight. Photo: scottkerrigan.com| Sea birds are some of the world’s best anglers; they have to be to survive. These hunters pursue the smaller forage fish that large predators, such as marlin, herd and drive to the surface. Even at some distance, birds can tip you off to the presence of marlin.

But not all birds are created equal as anglers seagulls and pelicans, for instance, don’t offer the same target-acquisition reliability as do terns, jaegers or petrels.

Birds on the hunt fly in a fairly straight line and with evenly measured, yet rapid, wingbeats. Watch carefully: These clues reflect how the birds track and react to the swimming direction of a marlin.

Birds holding above feeding billfish will hover while selecting their own targets, then tuck in their wings, extend their necks and dive-bomb into the sea. There’s very little chance of mistaking a “bird school” as they’re called by anglers when a flock of terns, frigates, jaegers or petrels is frantically circling, dipping, nose-diving, then piercing the surface, feasting on the forage fish.

THE BEHAVIORAL APPROACH

Just as learning bird behavior makes a better marlin angler, so does understanding the actions of surface-oriented stripies. When spotted, a marlin almost always exhibits one of four modes of behavior: jumping, sleeping, tailing or feeding.

- JUMPERS are the most difficult to coax into taking a bait, partly because most jumpers are singles and are sighted at some distance. They may be up just for a jump or two, before disappearing. By the time you arrive at the spot where a jumper was last seen, chances are it’s gone. Some observers feel that jumpers aren’t really interested in feeding anyway, but are cavorting and crashing to knock parasites off their bodies.

Still, on slow fishing days with little or no other surface activity, chasing an occasional jumper may produce that infrequent hookup.

On otherwise great fishing days, you can pretty well write off jumpers as they’re not worth the effort.

SLEEPERS are marlin that appear to be doing just that — sleeping on the surface. The fish is suspended almost motionless, typically with only the upper part of its tail fin showing and barely moving. When cast to, sleepers are unpredictable; some will simply stay put, while others appear disinterested and sink down into the depths. But enough will suddenly be jolted awake by a splashing live bait that you should never pass up a sleeper.

TAILERS are mobile fish, presumably migrating or cruising for a feeding opportunity. Tailers are often seen surfing downhill, using the energy and motion of an ocean swell to aid travel. Placid, tabletop-flat seas tend to produce more jumpers and sleepers, while tailers get active when a breeze roils the surface. Tailers are good bets to crash a bait. An attack seems imminent when the tail beat suddenly shifts from a steady, moderate-speed paddling to a series of excited, staccato-like whips of a marlin’s rudder.

FEEDERS are the most probable strikers, especially when two or more are encountered and are driven by feeding competition. Cyclical El Ni-o weather patterns increase summer and fall stripie numbers off Southern California and can gather marlin in packs ranging from pairs to a half dozen. Off Baja California, stripies sometimes hunt in aggregations of well over a dozen fish. A feeding scene is unmistakable: birds hovering, swooping and diving; baitfish jumping, attempting to escape; marlin flashing tails and bills, dorsals cocked forward, crashing and churning the surface into a frothy, swirling melee.

When a feeding frenzy erupts near your boat or you slide up on feeders that you’ve approached from some distance you’ve found nirvana. And in the excitement, the angler’s toughest challenge may simply be to retain composure and not backlash on the cast.

TAKE A BOW

To get a bait to a surface-oriented stripie, many anglers prefer casting from the bow. And since many marlin-outfitted sportfishers feature bow pulpits, these elevated casting platforms make the underhand lob cast easy to master.

The height above water of many pulpits allows an angler to dangle his bait and lob-cast it via a longer leader, generally at least the length of the rod itself (around seven to 71/2 feet, compared to the longer leader length used on a dropback-bait outfit in the stern). If possible, the skipper should approach the marlin from downswell, then slow the boat at such a distance that the boat’s slide takes the angler into casting range.

A well-placed lob cast aims for a spot six to ten feet ahead of and beyond the fish. A bait splashing down at that point will turn the marlin’s head and its attention away from the boat. Conversely, a bait cast between the fish and boat may spook or disturb the fish, or switch the marlin’s focus to the hull, not the bait.

Anyone serious about catching striped marlin should become an accomplished bow caster. It’s simply a prerequisite to consistent billfishing success. At marlin tournaments, I’ve seen top-notch angling teams compete in land-based mackerel-casting contests, during which contestants stand on an elevated platform and lob a weighted, vinyl “fish” into a filled wading pool. Even at a distance of 50 to 75 feet, it’s remarkable how many pro casters are dead on target inside a 72-inch-diameter ring.

| DORSAL DIVING VS. A NOSE JOB |

Two of the most popular methods of hooking a marlin bait (most often a live mackerel) are dorsal-hooking and nose-hooking. Nose-hooking (shown at left, top) can be accomplished either by inserting the hook point into the lower jaw of the bait, then pushing it upward to emerge through the top of the nose, or by inserting the hook point horizontally (not shown) or crosswise through the nose. Baits nose-hooked horizontally tend to live longer in the water, since the mackerel’s mouth is unrestricted for the water intake needed to “breathe” by passing water through its gills. Hooking the bait forward of the dorsal fin (an area some anglers call the neck) tends to make the bait go deeper, since the angle of pull from the line tilts down the mackerel’s head as it swims. Dorsal-hooking (shown at left, bottom) also helps keep a bait under water when slow-trolled almost at mooching speed as the hook position causes the mackerel’s head to act as its own diving plane.|

TAKE YOUR BAIT OUT FOR A WALK

If a stripie doesn’t strike a bow-lobbed bait the presentation isn’t over yet. As the boat continues to slow and slide, the angler walks his bait along the side of the boat while still free-spooling line, continuing the walk until stepping down into the cockpit. Then a thumb on the spool holds the line in place while the bait is towed, then soaked, 80 to 100 feet beyond the still-slowing boat.

A second angler is ready to reel in the trolling lines if a marlin takes the live bait. Often, a bow-baited marlin refuses the first offering, but reappears astern and takes a bait that has been walked into that position.

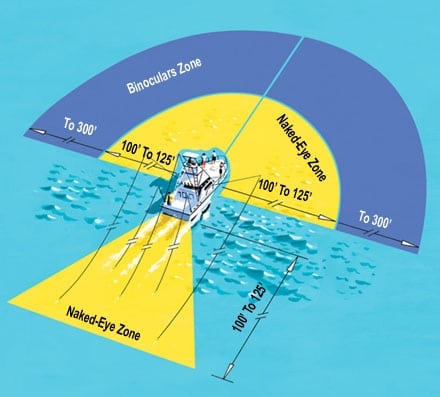

| SEARCHING BY ZONE |

| | Angling for striped marlin on the surface is more hunting than fishing: you’ve got to find fish to bait them. When searching, anglers are assigned specified zones to scan both near and far, with and without binoculars. The forward and more distant zones represent a 180-degree sweep off the bow and call for scouting with binoculars. This zone is divided in half (see illustration), with one observer watching the port quadrant and a second observer responsible for the starboard quadrant. Because many boats literally run over or pass by close-in marlin that anglers never realize were there, a second pair of anglers scans within the same quadrants, but using only their naked eyes and scouting much nearer the boat. A fifth observer is assigned the sternward zone a roughly 90-degree vision sweep angling out from both stern corners and encompassing the trolling-lure pattern and outward to 120-plus feet. This angler is responsible for detecting problems or fish in the spread. To minimize eye fatigue invest in a pair of gyroscopically controlled binoculars and beanbag cushions to lean on and steady the view.|