[Be sure to click through all the images in the gallery above.]

It was all better Back in the Day. We hear that phrase all the time. It’s become an adage, and the adage has a way of telling it like it is. For example, tarpon fishing was way better Back in the Day. Well, here are a few of my memories from the Day — what do you think?

Back in the day, spring mornings smelled the same as they do now and when I’d walk outside to hook up the trailer, the dew was just as heavy on my truck and skiff then as now. Ground fog lying along the Ingram Highway (into the Park) or along U.S. 1 to the Keys was and is still the indicator that the breeze would be light long enough to find them laying up. Bad coffee was still bad and good coffee hard to find at a quarter to 5 a.m. Poling into the wind did seem easier then — why is that?

Sharing the day with a friend was a tremendous part of tarpon fishing, and as you learned the ways of the tarpon, so did you learn the ways of friendships and the sacrifices necessary to maintain them. You learned that pushing away from the dock and all the daily trappings left just the two of you, at either end of a skiff, to be the men that you were and would become.

I was lucky in my younger days to have had such fishing friendships. They become the markers among a changing cast of markers, keeping us in our chosen channels.

John Emery, Chico Fernandez and Norman Duncan were such friends. We went to grade school and college together, survived dating and finding jobs, and watched each other become consumed with fishing. In the middle 1960s, we were night and day fishermen and the fact that very few others understood the depth of our illness drew us deeper into its symptoms.

The speed limit between Homestead and Key West was 70 mph. The bridges were extremely narrow back then and there were only two traffic signals between Florida City and the Garrison Bight boat ramp in Key West. We thought nothing of leaving home in the morning, fishing Key West all day and attending class at the University of Miami at night.

John Emery had a job working for a tackle component company owned by a prominent angler named J. Lee Cuddy. Lee would spellbind us with stories of giant tarpon eating flies the size of chickens. We had all caught plenty of small tarpon on flies along the Tamiami Trail canal, but these storied giants were quite another thing and the stuff of dreams that we knew, at some level, would eventually come true. Lee actually mentioned the names of places he fished, and later, the three of us would study them diligently on charts. We pumped Lee for tide information, fly patterns and whatever else he might be willing to share about fishing for the giants.

None of us knew or cared about which professional athlete wore number three on his jersey or what his annual salary might be. Our heroes became the cutting-edge guides of the times and the pioneers of fly-fishing for tarpon. As our impregnated bamboo fly rods were exchanged for the newer, hollow fiberglass ones and our oak dowel push poles gave way to glass vaulting poles, we were swept into the very highest levels of fly-angling in salt water.

From what we learned about tarpon tackle from Lee Cuddy, and from the selection of rod blanks and components in his shop, we built fly rods in Norman Duncan’s family garage. We would glue and shape cork handles, wrap the guides on with thread and apply spar varnish to the wraps and, sometimes, cast the rod in the street in front of Norman’s house — all in the same day. If longer drying time was needed for the varnish, we would cast the rods at night in the lighted parking lot at the University of Miami. It didn’t impress a single girl as I recall nor a single one of our professors.

When not doing homework, building rods or fishing, we found time to tie flies. The go-to patterns at first were Cockroaches, and Capt. Bill Smith tarpon streamers. Norman Duncan was a great tier, Chico was phenomenal — I was a laughingstock getting only somewhat better with the passing of decades.

Our source for tying materials was the Herter’s mail order catalog, which was the same place we got our duck decoys. We actually made our own vises out of vice grip pliers welded onto a metal dowel on one end and a C-clamp on the other.

We had rented 15-foot Challenger skiffs from a livery on Summerland Key for several years and became very friendly with the livery owner. John Emery bought a hull from him and enhanced it with cover boards, decks and rod holders. John and I bought a trailer and a 50 hp Mercury outboard from Bob Hewes and all at once we had a skiff that would follow us all around South Florida. Norman built his own skiff on an 18-foot Fibercraft hull and named it Xanadu. It was quite a skiff!

I found another Challenger hull and had it built up by Dan Groves, who did custom boat construction in South Miami, and bought my second Mercury outboard and trailer from Bob Hewes. Bob was always kind to us young fisherfolk and found ways to make it possible for us to purchase what we needed.

The skiffs not only were tarpon skiffs, but also often found themselves in bonefish and redfish depths as well as offshore in the Gulf and Atlantic seeing amberjack, cobia, grouper and sailfish coming over the gunwales, and although we each had our own skiff, we fished together a great deal of the time.

The phenomenon of fishing clubs entered our lives during those years. I became a founding member of the Miami Sportfishing Club with headquarters in the southwest section of Dade County. Lots of the fishing that we did was offshore but my heart was captivated by the shallows. Fellow club members Ralph Delph and Joe Robinson were of the same mind and the three of us spent lots of days exploring the lower Keys for tarpon country.

One morning, Joe and I made the early morning drive from Miami to Sugarloaf Key. We put out north to some banks near the open Gulf of Mexico where early in the year tarpon were given to lurk. We found them laid up by the hundreds along a single bank and enjoyed the better part of the day fishing them one at a time. The tide turned, the tarpon floated out into the Gulf, and it was over for us — the best tarpon day — ever.

We swore an oath never to reveal the location of the spot to anyone. Then, we re-swore the oath — never, no one! The very next week I went back to the spot with John Emery — never, no one!

When we approached the bank, I could see at a distance that another skiff was there. Impossible! It was Joe Robinson with Ralph Delph — never, no one! I recognized Joe’s little aluminum skiff, and at the same time, they recognized mine. Once we’d poled up onto the bank, Joe had slipped a bandana over Ralph’s eyes and was poling Ralph, blindfolded, down the bank. “I didn’t show him anything! He has no idea where he is!” Joe hollered through their combined laughter, and to this very day, we all refer to the spot as Blindfold Bank — I’d love to tell you where it is, but you know — never, no one!

Stu Apte’s name was known to me as he was an early pioneer of fly-fishing for tarpon. He lived and guided out of his home on Little Torch Key. His home could be spotted from the road and we would stop early in the morning and watch him and his anglers load up and leave the dock. It was the most flagrant form of hero worship. I noticed his cap, his khaki fishing slacks and shirt, even his shoes.

I had never met Stu, and wouldn’t for some years, and when I finally did, it had nothing to do with tarpon fishing. I hadn’t known, but Stu was a shotgun pointer, and a very good one at that. Ralph and I very seriously hunted marsh hens in Florida City and ducks in the Everglades west of the 20 mile bend at the L-67 canal. Ralph had met Stu and invited him to duck hunt with us. I found myself side by each with my hero, chest deep in a duck marsh, peering not over tarpon tails, but duck decoys! There was no talk of tides, fly patterns or casting technique, just the whistling of ringbill wings over the spread of decoys.

Stu became our constant hunting companion. I was actually reluctant to bring up the subject of tarpon, and finally, the next year, Stu invited me to fish with him in the Lower Keys. If someone had told me that I could fly — “Flip, all you have to do is flap your arms and you’ll be in the air” — I could not have been more excited!

Reality could not have been better than my dreams of fishing with Stu — but it was. The day was sensational and much like a masters course in tarpon.

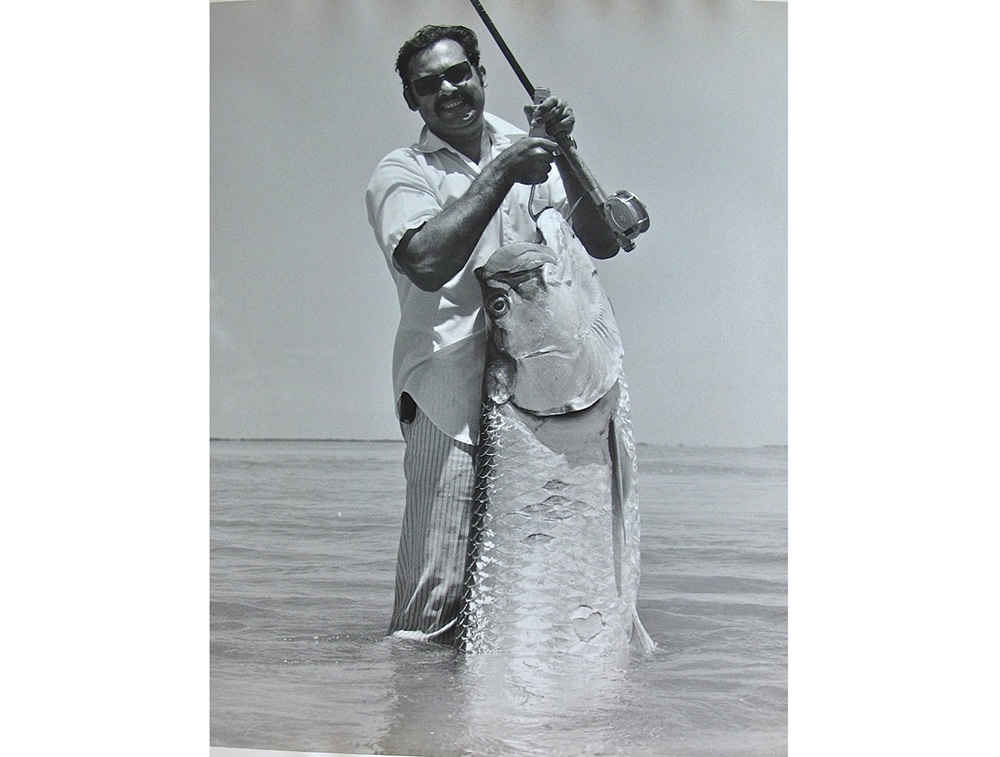

Stu introduced me to outdoor films in Key West not long after he caught the monster tarpon in Pearl Basin. He was a saltwater pro staffer with Evinrude Outboards and had sold the company on the idea of a giant tarpon show fishing from a canoe with a 3-horsepower Evinrude motor.

We arrived at Key West with the canoe and the 3 hp engine, and met the film crew and Keys guide Woody Sexton, who would pole the camera boat. After launching at Garrison Bight, we repaired to a turtle grass meadow west of Key West and could see fish rolling long before we reached the pocket of the basin.

There was a light chop and the 17-foot canoe bobbed a bit as I paddled Stu into position for a cast at a laid-up fish. Its tail and dorsal spike were out of water, and from a sitting position in the front of the canoe, Stu made a brilliant cast, landing arm’s length in front of the fish. He let the fly sink for several seconds, gave it a single twitch kicking the splayed hackle feathers of the fly seductively, and the apparently sleeping tarpon launched itself at the fly. His entire giant head left the water as his mouth closed on the fly and Stu came tight with the hook set. The very next thing that we saw was a giant tarpon make a single, greyhounding leap in our direction. The sound of his landing in the middle of the aluminum canoe was deafening. The impact was shocking! The gunwales immediately collapsed; the canoe filled with water and slid beneath the surface, sinking by the weight of gear, folks and the little outboard!

We were quickly rescued by Woody and the camera boat. The water was clear and we soon dove our gear up off the bottom and refloated the canoe. The little Evinrude was well baptized in salt water and would not restart.

Back at the motel, as Woody and I made repairs to the canoe and tackle, Stu was on the phone with Evinrude. They sent a new motor by courier from Miami and the next morning we were back in the film business.

Lefty Kreh moved into our neighborhood in the middle 1960s to manage a local but very large fishing tournament sponsored by the Miami Herald. All of us fished the tournament avidly — especially the fly-fishing division. We considered ourselves very expert fly-fishermen, and perhaps we actually were. What we were not was expert fly-casters. Lefty changed all that for me and others. Actually living in his neighborhood made it particularly easy for me to drive Lefty insane with questions and surprise visits to his house for lessons. Lefty was never too busy to stop whatever he was doing, which was always something, and make time for me.

Through all the years, Lefty and I fly-fished for tarpon countless times. He particularly loved the small ones deep in the Everglades. We filmed an episode of the Outdoor Life television series together along the ocean side of the Keys. Lefty hooked a giant on camera, and as the fish made its initial run and series of jumps, the fly line springing up from the deck slung a double loop around one of Lefty’s legs. The fish continued its run as Lefty hopped around on one leg, finally lying down on the deck to untangle the tarpon’s handiwork, tears of laughter making the untangling process harder still.

When we all recovered from the episode and the tarpon continued his northerly migration, the director of the show said, “Don’t worry, Lefty, we’ll cut out all the scenes of you being tangled in the fly line so that you’re not embarrassed.” “Bullshit,” replied Lefty. “You leave those scenes right where they are!” A lesson for me in humility from a man who wound up friend, mentor (a much overused word but in this case true), co-worker and shaper of my life in many ways.

On that very same day, in the skiff next to us, Rod Harrison, Australian fly-fishing legend, caught his first giant tarpon. In the middle of the fight, the reel he was using malfunctioned and he finished the protracted battle with no drag at all, using his hands on the line and reel to subdue the tarpon.

We gathered up that evening at Bill Bishop’s fishing cabin and, under the spell of the day’s excitement and the mild influence of adult beverages, learned Australian fishing knots from Rod and teased him about how long it took him to land his first tarpon. Although the fishing day was stellar, it’s the evening off the water that I remember most. Amongst those players, it’s impossible not to hurt yourself laughing. Sam made his famous clams linguine and Lefty sulked in the corner eating soda crackers and chiding us for putting clams and suchlike in our stomachs.

I can recall hundreds of stories that comprise the “Good Old Days” of tarpon fishing and the many pioneers of the sport that I was fortunate to know and share skiffs with: Rob Fordyce when he was 13 years old, Al Pfleuger, Jim Brewer, George Hommell, Jack Brothers, Hank Brown who would actually talk to me on the radio, Fredrick Remington, Rick Ruoff who showed me a fabulous tarpon spot, Jimmy Albright who tied turk’s heads on my kill gaff, Eddie Wightman who I dove conchs and chased turtles with, Cecil Keith and Cliff Ambrose who I frog-hunted with in the Glades, Roy Lowe and Joe Saldino who helped me get my boat chair back from the hippies (another story), Bill Hegle and Nat Ragland, guides who I fished the Gold Cup with, and so many others, prevented from mention by the space allotted for this story. They were simply characters from my own “Good Old Days.” You will have your own and I urge you to take notes, take photos and take chances, remembering that you will never regret things you do nearly so much as those you don’t. One day, years from now, and it happens in a blink, you will find yourself Back in the Day.