A conservation movement aimed to mitigate climate change, enhance biodiversity and ensure equitable access to outdoor spaces sounds like program that everyone, including anglers, can get behind. These goals are part and parcel of the so-called 30×30 initiative, a global movement conceived and promoted by environmental groups to protect 30 percent of the ocean and land by the year 2030.

Yet, sportfishing communities from coast to coast have grown skeptical and suspicious of the political influence and true intent of the forces behind the movement. Those forces include well-financed environmental groups such as the Audubon Society, Azul, Defenders of Wildlife, and the National Resource Defense Council. Strong and determined, these organizations have already set the wheels in motion for 30×30 programs at federal and state levels.

This is the story of one of those states — California — where implementation is moving ahead with greater speed than anywhere else in the country, largely because proponents aim to set precedent here for implementing 30×30 throughout the US and around the globe. Yet the process in California is far from complete, and outcome not quite clear. While no one’s exactly sure how it will turn out, the experience so far might provide guidance to angling groups facing 30×30 initiatives in other states.

But before heading west, let’s take a closer look at 30×30 and how proponents envision its implementation, particularly in coastal waters.

Defining 30X30

The National Resource Defense Council — one of the most visible environmental groups behind this initiative — defines 30×30 as “… protection of at least 30 percent of the world’s oceans and 30 percent of all lands and inland waters by 2030.”

The goal, according to the NRDC’s 30×30 fact sheet, is to safeguard air and water quality, protect our food supply and health, prevent mass wildlife extinctions, and protect treasured natural spaces.

While that sounds fine, it’s the single-minded manner in which environmental groups propose to achieve these goals in ocean waters that raises the hackles of anglers. The NRDC fact sheet states: “’Highly and fully protected’ MPAs (Marine Protected Areas) are the most effective (means), providing safe havens for ocean life to recover and thrive without pressures from extractive activities like industrial fishing and oil and gas drilling.”

More MPAs

Interestingly, the NRDC fact sheet fails to discuss critical ocean issues such as minimizing pollution due to agricultural or urban runoff or sewage spills. Nor does it recognize sustainable and proven fisheries management tools such as seasonal closures or catch limits as legitimate conservation measures.

“Their end goal is to expand the MPA network,” says Bill Shedd, CEO of AFTCO and chairman of the Coastal Conservation Association of California. “It’s not about biodiversity. It’s just MPAs. Proponents of 30×30 want to see as little fishing as possible. They think that sport fishermen are the problem.”

Shedd points out that no-take MPAs remain unproven as ocean conservation tools. He has aggregated on the AFTCO website more than 10 scientific and mainstream articles, including a paper by Shedd himself, to support this argument.

“A deep dive into the MPA studies shows that US-based no-catch marine protected areas do not increase fisheries productivity, and that current fisheries management tools are far superior at achieving the goal,” Shedd states in his article.

Western Battle

In the spring of 2020, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, proponents of 30×30 attempted an apparent sneak play in the California Legislature with the introduction of Assembly Bill 3030 (Rep. Ash Kalra, D, Santa Rosa). Many in the sportfishing community believe that the sponsors exploited Covid restrictions and concerns to try to pass the bill before opponents could gear up. Whether the timing was intentional or not, the sportfishing community was caught off guard as AB3030 swiftly flew through its first two committee hearings and was approved by a majority vote of the Assembly within a few weeks of its introduction.

The balance began to shift as AB3030 reached committee hearings in the state senate. The Coastal Conservation Association of California (CCA CAL) along with a coalition of other stakeholder groups ramped up opposition efforts through lobbying arms, and mobilized anglers and other outdoor enthusiasts to voice concerns to their state senators through aggressive outreach programs and online petitions. And it worked. While AB3030 passed through the first senate hurdle in the Natural Resources and Water Committee, it stalled in the Appropriations Committee and failed to move on to a vote in the upper house.

Executive Edict

While AB3030 effectively died in committee in mid-August 2020, the big-money environmental groups behind 30×30 staged an end-around play. They had ear of California’s Governor Gavin Newsom. The groups, along with Rep. Kalra, convinced Newsom to use his executive powers to bypass the legislature. In a stunning example of gubernatorial over-reach following the defeat of AB3030, Newsom signed Executive Order N-82-20, committing the state to the principles of 30×30.

Pathways Document

Newsom’s executive order directed the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA), along with its sub-agency, the Ocean Protection Council (OPC), to engage and collaborate with key stakeholders, including fishing organizations, and other state agencies to develop and report strategies for achieving the goals of 30×30. The report eventually gained the title, Pathways to 30×30.

Interestingly, shortly after the executive order was issued, CCA CAL’s Mark Gorelnik, Chairman of the CCA CAL Government Relations Committee, and Wayne Kotow, Executive Director, were contacted by the Director of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Charlton Bonham, who promised that CCA CAL, as a key stakeholder in the 30×30 process, would have a “seat at the table” during the development of the report. That did not occur.

“CCA CAL did not get a seat at the table, because there was no table,” said Mark Gold, then director of the Ocean Protection Council.

Instead of CCA CAL having the opportunity to provide meaningful direction, the CNRA and OPC scheduled public meetings, in this case, nine regional workshops (with 150 to 350 participants in each event), plus two topical workshops with up 467 and 283 participants each. There was also an online questionnaire. Following publication of the draft, there was also a 60-day period for public input.

CCA CAL participated when possible, but Gorelnik believes that these opportunities for input are largely perfunctory in nature. “We expected measures that would allow us meaningful input, as we were promised a seat at the table by Director Bonham,” he explains. Gorelnik describes the actual opportunities for input on the Pathways document as more symbolic than substantive.

Like Language

A draft of Pathways to 30×30 emerged in December 2021 from the California Department of Natural Resources, and the 72-page document held disappointment for angling groups such as CCA CAL.

“It is no coincidence that the draft of the Pathways document and AB3030 have very similar language,” Gorelnik says. This serves as an indication that input from proponents of 30×30 held the greatest weight in the development process, he feels.

The document’s definition of conservation as it relates to 30×30 has emerged as a major point of contention. It defines conservation as: “Land and coastal areas that are durably protected and managed to support functional ecosystems, both intact and restored, and the species that rely on them.” A key phrase here is “durably protected,” and it’s not precisely defined in the document.

Yet the authors (staffers at the CNRA and OPC) seem to know it when they see it, to paraphrase the US Supreme Court. A great concern in the angling community is that it includes only areas that forbid fishing. And therein lies the sportfishing community’s skepticism of the true intent behind 30×30 and suspicion that the political forces behind the movement are anti-fishing.

Ambiguous Phraseology

The good news is that some of California’s existing MPAs permit fishing, while others limit fishing or forbid it all together. The bad news is that the state’s MPA network is calculated in the document to cover 16 percent of the California coast and offshore islands. Based on this, it will require nearly twice as many MPAs to meet the goals of 30×30.

CCA CAL has officially protested the decision to include only state-managed MPAs in its definition of durably conserved, as there also exists a number of National Marine Sanctuaries along the coast and offshore islands, which if included, would bring the percentage of ocean waters much closer to 30 percent. Only time will tell if the CNRA eventually pays heed to CCA CAL’s protest and accepts the National Marine Sanctuaries as being durably conserved.

Lip Service or Sincere?

The Pathway document seems to contain another ray of bright news. In the section titled “Access to Nature,” it states: “Conservation must consider a broad range of community needs and priorities … fostering active recreation including hunting, fishing, hiking, boating and more.”

That would seem to indicate that angling and 30×30 can coexist, but California angling groups have heard such platitudes before, specifically during the implementation of the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA) more than a decade, but in the end lost big sections of the coast and offshore islands to no-take fishing MPAs.

“As far as I am concerned, this is MLPA 2.0,” says Shedd.

What’s Next?

In 2022, the final Pathways to 30×30 document was published, and it contained no substantive changes from the draft document. The vague language regarding “durably protected” MPAs still stands.

However, the California regulatory agencies charged with 30×30 implementation — including the CNRA and the OPC — have been obliged to put 30×30 development on hold with regard to coastal waters. This is because much of the coastal planning hinges on the findings of a long-anticipated Marine Protected Area Decadal Management Review.

This study was mandated in the implementation of California’s Marine Life Protection Act that established the state’s MPA network in 2012. Intended to evaluate the effectiveness of the MPAs and provide guidance for changes in the network, that 137-page study was released in January 2023 and is currently under review by CCA CAL and other stakeholder groups.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) in coordination with the OPC, California Fish and Game Commission, and the Resources Legacy Foundation hosted a MPA Decadal Review Forum on March 15, 2023, in Monterey, California. The idea is that the findings of the study and stakeholder input will help guide the 30×30 process.

After that, it is anyone’s guess as to how the 30×30 process will proceed or what the sequence of events or calendar of opportunities for public input will look like. “An executive order is not exactly a democratic process,” Gorelnik points out. “It’s not like the legislative process that requires opportunities for comment, public debate and voting by lawmakers.

“It’s just the governor telling his state agencies to get it done, and staffers are obliged to comply, or get fired.”

Angler Outreach

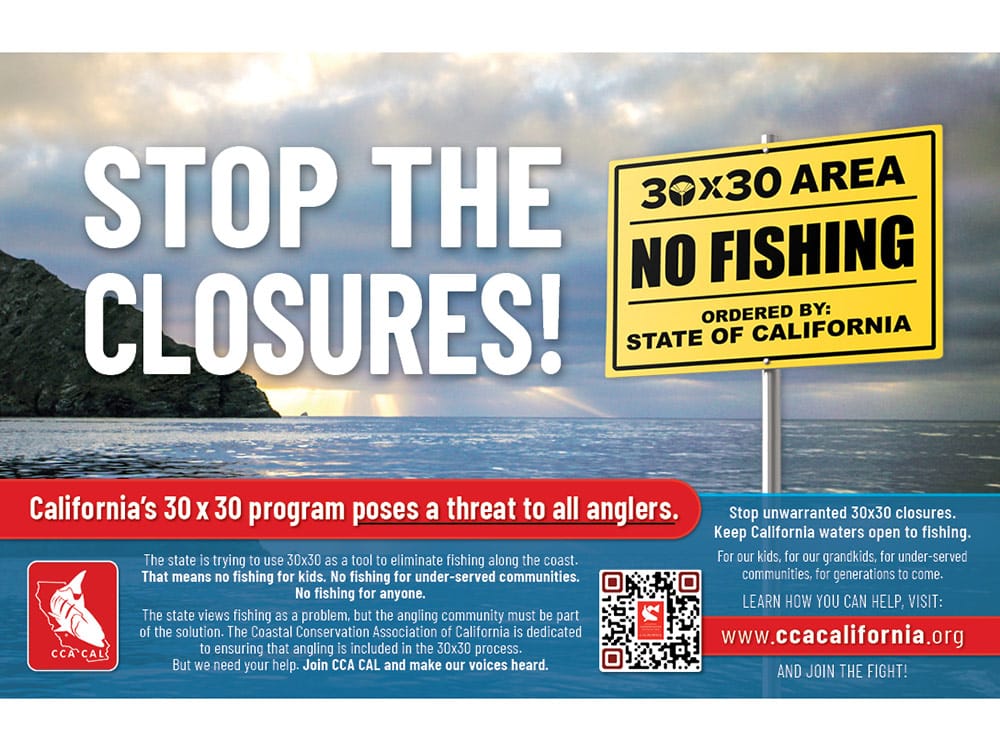

In the meantime, CCA CAL is not sitting on its hands. It has gone on the offensive, launching an aggressive multi-media campaign to generate public awareness and opposition to the establishment of more coastal no-fishing areas within California’s 30×30 plan.

The campaign kicked off in February 2023 with a “Stop the 30×30 Closures” theme, encouraging anglers and others to help battle against the potential for 30×30 fishing closures by joining and contributing to CCA CAL.

“The State of California views anglers as a problem, but in reality, we are the original conservationists with a vested interest in strong marine ecosystems and biodiversity,” Kotow adds. “We are committed to working toward solutions that conserve marine resources and at the same time preserve coastal fishing access. That includes fishing access for kids, for under-served communities, for everyone.” Other sportfishing organizations are launching separate campaigns to bring to bear political pressure on California politicians and regulators to include recreational fishing in 30×30 areas.

Only time will tell what ultimately occurs in California, but the fate of recreational fishing as we know may well hang in the balance. With 30×30 programs underway in other states and at the federal level, no-fishing policies adopted in California could well spread to the rest of the country. States such as New York, New Jersey, Oregon and Washington, for example, often follow California’s lead.

But if CCA CAL’s response to the potential for coastal fishing closures in the 30×30 process is any example, the angling community is not going down without a fight.