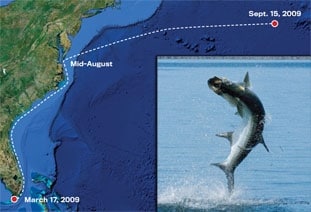

When satellite tag T-118 began transmitting data on Sept. 15, 2009, it had traveled more than 2,200 miles from where originally attached to a 98-pound tarpon caught on fly aboard my boat six months earlier in Florida Bay. This could very well be the greatest distance ever covered by a tagged tarpon, according to Dr. Jerry Ault, who heads the tarpon research program at the University of Miami, which tagged this fish, one of 137 silver kings tagged since 2001.

T-118 began transmitting data precisely on schedule, six months after the catch. At the time, it was located well into the North Atlantic (near 40.5 degrees north and 54.5 degrees west), only 250 miles southwest of the location the Titanic sank almost 100 years ago.

Now the question begs: How did it get there? And did it remain on the tarpon throughout the entire six months, or did it pop off at an earlier date and drift the remaining distance?

Unfortunately, T-118 had not been physically recovered at press time, and considering its location in the northern reaches of a huge ocean, it may never be found. If that’s the case, much of the data permanently stored in memory will remain unavailable.

But a significant portion of that data – including temperature, depth, light levels and salinity – was successfully uploaded to the satellite as soon as the tag began transmitting.

T-118 transmitted for 10 days before its batteries ran out. That’s usually enough time for recovery by a search party, had it washed up on a beach. That obviously did not happen in this case (although some tags are eventually recovered and returned by beachcombers long after battery failure).

The satellite-recovered data did provide enough information to reliably track more than 1,000 miles from south Florida to Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay by mid-August, not an unusual destination for some of these coastal wanderers. Unfortunately, not enough information and data exist to explain exactly what happened after that.

After leaving Virginia, T-118 traveled at least another 1,200 miles eastward before it began uploading to the satellite. Perhaps not ironically, this is the same route followed by the warm current of the Gulf Stream – and its temperature in the mid-70s is well within a tarpon’s comfort zone.

PATs have proven that tarpon are indeed incredible long-distance travelers, and it is entirely possible that this fish went the distance. It might well have been under way to some unknown destination when the PAT finally popped off. (After all, folks are still scratching their heads about how the 130-pound tarpon caught near Cork, Ireland, in the mid-1980s got there.)

PATs are tough, durable instruments, and Dr. Ault says he would not be surprised if T-118 does turn up on some European shore years from now.

Until then, we’ll just have to guess as to what exactly happened.