Offshore jigging has really taken off in the past couple of years. Sure, some early adopters have been jigging with metals for decades, but it was never something utilized by the masses. That’s changed in a big way. Today, the vast majority of offshore boats—charter and private—have a number of jig rods rigged and ready. Plus, new styles of jigging are developing in real time.

“The ease at which anglers can target different areas and species with one or two compact jigging setups is attractive,” says Ryan Morie, a Florida-based fishing content creator on YouTube. “Let’s say anglers are headed out of South Florida to run-and-gun for dolphin. After catching a limit, they’re probably close to the tilefish grounds. Forget all the electric deep-drop gear. Have a slow-pitch rod and a few jigs ready to go, drop down, and add some tiles to the box.”

Metal jigs catch just about everything, from grouper and jacks to striped bass, tuna and yellowtail. Jigging can also be the most effective way of targeting fish in certain situations, so it’s definitely a skillset to refine.

“I prefer to slow-pitch only when it makes sense,” Morie says. “Maybe we’re targeting bottomfish in 300 to 500 feet of water, and the current is too strong to fish a bottom bait. Maybe there’s tuna marked on the depth finder at 250 feet, and it’d take too long to get a live bait down. The speed at which you can drop a jig and fish an area is unmatched.”

In the future, Morie thinks that jiggers will start exploring deepwater applications for out-of-the-box species. “There have been a few swordfish landed on slow-pitch gear, and I think that might become a much more popular way to target them,” he predicts.

Snap to Attention

What’s the best way to jig if you’re marking a school of fish at specific depths but they’re not all that active? Growing numbers of Northeast anglers are using the technique of snap jigging to catch striped bass and other species.

“It’s a hybrid of slow-pitch jigging and ‘twitch’ jigging,” says Ross Gallagher at Hogy Lures. “To be clear, twitch jigging is just a technique of twitching the rod tip so that the jig bounces up or down in a confined area.”

Snap jigging utilizes an aggressive snap of the rod, but the jig doesn’t cover great distances vertically. “Wherever you’re marking fish—on the bottom, just off the bottom, or suspended—get that jig into the zone,” Gallagher says.

Snap jigging requires the angler to make an aggressive pop with the rod, then allow the jig to free-fall on a semi-slack line. But pay close attention during the fall because that’s when the bite is most likely to occur. About 70 percent of bites occur then, Gallagher says, so watch for a subtle “tick” or even for the line to go slack completely.

“You really want to use this technique when the fish are keyed into a specific depth,” he says. “There’s really not a lot of vertical movement to the jig, just 1- to 2-foot snaps, almost like you’re teasing them.”

Hogy’s Sand Eel jig is what Gallagher uses for striped bass. He wants his jig to look like an injured sand eel that’s having trouble escaping. He uses light spinning tackle—3000- to 6000-class spinners, 15- to 30-pound braid, and 30-pound fluorocarbon leader—because he’s often fishing open water without structure nearby.

Besides stripers, Gallagher uses snap jigging for tuna and even bottomfish suspended off the bottom or over wrecks.

Ready With a Knife Jig

West Coasters are slaying Pacific bluefins with metal knife jigs. For daytime fishing, knife jigs get the nod when there’s little to no action on the surface but a consistent mark of fish from 150 feet or deeper. Tuna might not touch the live bait, but steady jig action in front of their faces can provoke a furious bite.

Jeff Neubauer, founder of California-based Chasing Pelagics, has noticed that his best vertical jigging happens at night.

“Look for winds under 15 knots. Anything more than that will be tough to keep your line straight and vertical,” Neubauer says. “I really like four to five days after the full moon for night bites.”

Any skittish bluefin behavior vanishes when the sun goes down, and “you can nearly fish with rope because they can’t see the line size,” Neubauer points out. Anglers have different go-to jigs, and there’s plenty of debate about the best design.

“I like the longer pencil—style or knife-shaped jigs with very little surface profile,” Neubauer says. “There are times when bluefins only want smaller—profile jigs—more often during the day—and that’s when I’ll switch to the 200- to 250-gram size with a glow-dot pattern.”

As far as setups, there are three main West Coast options used consistently. The first is a heavy, traditional rail-rod setup for nighttime fishing: a 7-plus-foot stick matched with a Penn Fathom II 80 lever-drag two-speed and 130-pound PowerPro Depth Hunter braid. “Knowing where your jig is in the water column is the most important part of the technique,” he says. “I connect the main line to a pre-made custom leader with a split ring at the bottom to attach the jig.”

Neubauer’s daytime setup is similar to his rail rod, but a lighter version with an 8-foot rod, 80-pound braid, and size-30 lever-drag two-speed conventional. He marks his line using a black marker in 1-foot-long sections to help record depth while jigging. The third setup is a “noodle” rod setup for speed-jigging techniques. Pair the short, parabolic rod with a narrow single-speed, high-capacity reel with an extra-long handle. Pumping and retrieving your line while speed jigging creates a flutter pattern on the wind up, a different action than what bluefins glimpse on the drop.

“The most important part of fishing the knife jig is making sure your line stays vertical,” Neubauer explains. “If my line starts making more than a 15-degree scope, I switch to a heavier jig or try casting downhill so that my line is vertical by the time it gets to the target depth. The baseline is 1 gram per foot of depth.”

Most of the time, 300- to 400-gram jigs work, but occasionally 500 grams are necessary. Neubauer usually fishes two assist hooks at the bottom of his jig, but he’ll add an additional single assist hook at the top of his longest jigs. The idea is, once bit, keep winding as fast as you can, and those bottom hooks will sink in too.

“Almost all of the bites come on the drop, and the line will go slack,” Neubauer says. “You have to wind as fast as possible to get tight because the fish is swimming directly up. Usually, if a school is feeding, that first jig down gets bit, so a fast descent is very important. Butterfly jigs might work as well, but the knife jig gets there quicker.”

Heavy-Metal Pitch

Deepwater species such as golden tilefish are suckers for squid, mahi bellies or chunks of baitfish on two-hook rigs. Turns out, you can use metal jigs to catch them too. But you must have the right tackle.

“When it comes to deepwater jigging, the most important thing with jig selection is to match the weight of the jig to the speed of the current,” says Viktor Hluben, of Landshark Outdoors, a YouTube channel. “I’ve caught deepwater tiles on short, stocky jigs and long, slim jigs. I prefer a longer jig just because it gives off a bigger profile, imitating a squid.”

The trend of dropping deep with metals has rocketed in recent years. Some days bait will 100 percent out-fish the jig, but other days, a jig is the only thing that gets the bite, likely as a reaction strike.

“I have noticed that big fish especially like the jig,” Hluben says. “Fooling a tilefish and feeling that strike is much more exciting than pushing a button on an electric reel.”

Jigging in deep water can be tough to master initially, so the two most important factors for success include choosing the proper-weight jig to maintain a vertical line angle and to fish with a thin-diameter braid. If you can’t keep your line vertical, go up in jig size until you’re successful. Also, the deeper the depth, the thinner the diameter line.

“I stick to 15- to 30-pound braided fishing lines paired with 300- to 1,000-gram jigs, depending on the current and drift,” Hluben explains. “When jigging deepwater fish, you’re not racing them to the surface. There is no need for heavy braid or tight drag; it’s a steady finesse-style fight to the surface.”

Most anglers target tilefish in 600 to 1,000 feet of water, but Hluben has had his best luck in the 900-foot range. He uses both hand-crank and electric reels. Anything deeper than 800 feet gets a motorized reel such as the Daiwa Seaborg. “I prefer to use the motor-assist reel when fishing on headboats,” Hluben says, “because it allows for quick retrieval of the jig when changing spots or getting out of the way of other anglers.”

Keep It Surface Level

After a prolonged winter, anglers might forget the ecstasy of a good surface bite. One option that reignites Northeast anglers is the epoxy jig, such as the Glass Minnow by Savage Gear.

“The metal jig is epoxy—coated to give it a larger profile and slower fall rate,” says Sam Root, with Savage Gear. “It allows the jig to stay near the surface, mimicking a school of small baitfish being harassed. The jig comes with a swivel to prevent line twists.”

Up North, epoxy jigs are a staple for inshore casters targeting stripers, false albacore and bluefish. Down South, anything that eats rain bait is a likely target.

“One of the great things about metal jigs is the ability to cast far and cover a ton of water,” Root points out. “Not only does this get your lure in front of the fish, but it also allows your lure to stay in the strike zone.”

Expect times when your surface jig touches down on the water and gets hammered immediately. The fish are aggressive and the fishing is easy. Think of a bluefish blitz or tuna foamers. But sometimes they need a little convincing.

There are two main variations to working a metal casting jig. One is to start cranking as soon as it lands, often with a speedy retrieve. Burners such as Atlantic bonito and false albacore prefer this. The other variation is to reel and let the jig flutter down like a wounded baitfish. Offshore species such as mahi love this type of action. And different types of surface jigs from different manufacturers impart different actions. Halco, Shimano, Daiwa, Hogy and plenty of others produce unique surface metals. For the old-timers, you might remember models like the Hopkins No=Eql, Luhr-Jensen Crippled Herring and Charlie Graves Swimming Tins.

Getting that bite depends on the feeding mood of the fish. If one type of action is lackluster, it’s up to the angler to figure out the puzzle. Match the hatch in size, but be ready with varying color options. For light jigs, spinning tackle rated for 20- to 30-pound braid offers the angler plenty of line capacity and casting distance. With heavier jigs for targeting larger species, use a casting setup that handles 40- to 50-pound braid, Root says. A longer rod helps with casting distance.

Tip: Don’t Forget the Skirt

“It’s all about the trailer,” says Capt. Gerry Mahieu, of Huntington Beach, California. He’s talking about the increasing numbers of jigs that incorporate skirts and trailers, such as the Daiwa Rock Rover metal jigs. Mahieu fishes areas near Catalina Island for lingcod, salmon grouper and vermilion rockfish—and this style of jig catches all of them.

“Salmon grouper will eat anything, but the lingcod requires a bit more action with the Rock Rover jigs,” Mahieu explains. “Fishing vertically, keep the jig near the bottom. Drop it down, lift a couple of feet—you don’t need to impart too much action.”

Mahieu ties to the narrow end of the jig, although there are multiple tie points. “This way, the jig drops fast like a teardrop, but it also prevents the hooks from catching on the leader,” he says.

And for the deepest water—Mahieu fishes up to 650 feet—he’ll use an electric reel such as the Daiwa Tanacom with his clients. Using 30- to 40-pound braid, 25-pound fluoro leader, and jigs up to 200 grams, the electric really shortens the fight time of getting a fish back to the boat.

Tip: Squid Lures Are Hot Again

Squid lures are so hot right now that dealers are taking them out of bargain bins and putting them back on the wall at full price. That’s economics, baby. Nomad has one of the most popular baits today. If you think of Nomad’s Squidtrex as a jig, one of your best bets is to try the fleeing-squid technique: Drop to the bottom and give it three to four fast rips up. Then stop it dead. But Nomad’s Damon Olsen will tell you that the lure is way more versatile.

“It works when bottomfishing in 300 feet of water for snapper. It works trolling for tuna. It works in 10 feet of water casting for striped bass, or in 100 feet casting at yellowtail,” Olsen says. “It’s all about versatility, and literally any fish that eats a squid will eat it.”

The temptation is to move a squid jig too much. The bait tracks well in the water, so using conventional tackle for deepwater reef fishing and spinning gear when casting are both equal options.

“Guys are catching fish when casting, jigging and even slow-trolling,” Olsen says.

Tip: Micro Meals

Bottomfishermen used to obsess about getting the best bait when headed out to the local wrecks and reefs. That’s still somewhat true, but another technique is quickly growing in popularity: micro-jigging.

“Micro-jigging is similar to slow-pitch and speed jigging; the only difference is your setup will be significantly lighter to accommodate the action of a small jig,” Hluben says. “We are talking about 10- to 20-pound braid on 3000 to 5000 spinning reels (or small 1500-size conventional jigging reels).”

Use a finesse-style rod with a fast taper to really pop the jig up and down. The rhythm of micro-jigging is nearly identical to regular jigging—there’s just less force and effort involved by the angler. Just about everything eats a micro-jig, including full-size snapper, grouper and fluke. But those other species that inhabit the wrecks that often require chunk baits are also fair game.

“For nearshore reefs in 60 feet or less, micro-jigs work great on light to no-current days,” Hluben says. “They can be jigged super-slow or fast and aggressive to the surface.”

Mustad offers Zippy and Traceshot jigs as lightweight as 15 grams, each rigged with an assist hook. Expect fast action, paired with true mixed-bag fishing.

Tip: Mod Your Jig

A ball-bearing swivel is your best friend when speed jigging—use it to prevent line twist. One way to add a swivel is as the connection point between the main line and leader. The purpose is obvious: to help stop line twists and preserve the action of a jig.

“Metal jigs designed for horizontal casting often incorporate a hook at their tail end,” points out George Poveromo, longtime Salt Water Sportsman contributor. “In this case, one could always add a ball-bearing swivel by first affixing it to a split ring, and then attaching the split ring to the eye of the iron.”

A Trick From Fresh Water

Here’s a way to give your jig even more flash. Some treble hooks are now sold with extra bling. VMC introduced a series of bladed O’Shaughnessy short-shank treble hooks with chrome blades.

“These blades add a bit more vibration and flash to an iron,” Poveromo says, “which could push a reluctant fish into striking.” So far, Poveromo’s had success with mackerel and grouper, but he believes that modification is applicable for most types of jigging.

Tip: Yo-Yos and Scrambled Eggs

If you weren’t already familiar with the tactic, you might ask, “What the hell does yo-yoing have to do with jigging?” Turns out, yo-yo jigging is one of the best methods to catch hard-fighting yellowtails. Angler Erik Landesfeind, a contributor for Salt Water Sportsman, has mastered the technique off Southern California.

“Yo-yo fishing is the best approach when you’re metering yellowtail but not seeing them feeding on the surface,” Landesfeind says. “This is the number-one go-to presentation for early-season yellowtail that haven’t set up on structure spots already.”

How do you yo-yo? First, drop the jig down to the zone where the fish are being marked. “The retrieve is fairly basic; just wind it as fast as you can,” Landesfeind says. “If you’re not getting bit, throw in the occasional pause after a few turns of the handle.”

Yo-yo irons—at least the majority of the market—are made by just a few companies. “Most anglers go with a Tady 9 or Salas 6X Jr.” Landesfeind says. “These jigs are preferred when the fish are keyed in on smaller bait or when there isn’t much current. The go-to larger jig is the Tady 4/0. All of these jigs are heavy models, different from surface irons. My favorite colors are mint-and-white and scrambled egg (a mix of brown, yellow and white).”

Read Next: Slow-Pitch Jigging Tackle Explained

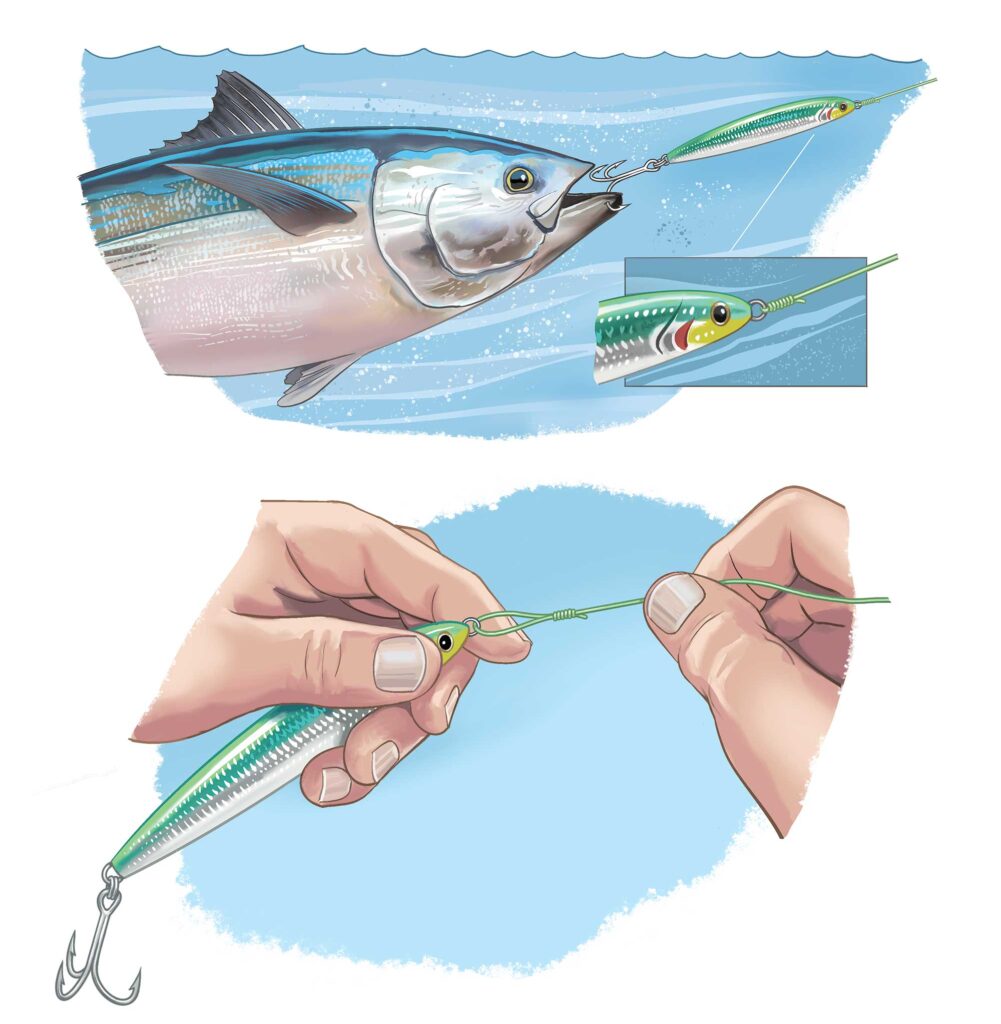

Tip: Use a Uni-Loop Knot for Big Tuna

Small jigs such as the AFTCO Blue Fever 60g Crossbreed have proven particularly effective when casting to schools of sizable bluefin tuna off the coast of Southern California.

“To enhance the action of the small lures when using heavy leaders such as 80-pound-test fluorocarbon, try using the uni-loop knot,” says Jim Hendricks, our West Coast and electronics editor. “Tie it just like a typical uni-knot, but don’t cinch it tight. Instead, pull it down to create a small loop, then hold the knot solidly between two fingers while pulling hard on the main line.”

This sets the knot. Leave a bit more tag than you might with a regular uni-knot.

The loop enhances the fluttering action as the lure falls, as well as the swimming action when retrieved.

“When a big tuna bites and you set the hook,” Hendricks explains, “the knot instantly cinches tight, closing the loop and minimizing line wear that might cost you a fish during a prolonged fight with a powerful bluefin.”