“I was hoping to fish tight to shoreline structure today,” said Capt. Ryan Kane of Southern Instinct Charters in Fort Myers, Florida. “Unfortunately, we have a red tide bloom spreading across this cove, so we’ll have to make a little adjustment. Hold on tight.”

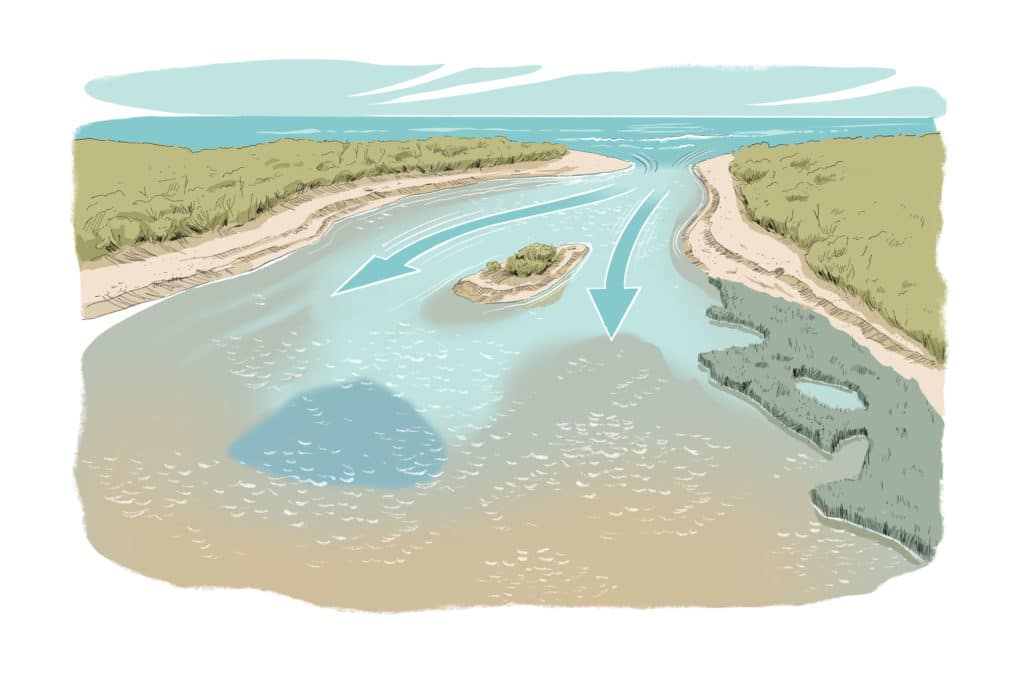

Kane pushed the throttle forward and pointed the bow toward open water in Pine Island Sound, where a small shoal awaited a mile away. The shallow waters, he reasoned, would be clearer due to stronger tidal flow, and redfish and snook were likely to cruise the perimeter in search of crabs, shrimp and baitfish during the early-morning flood.

Kane’s theory proved on the mark. After dropping the hook, it took less than 15 minutes to connect with our first snook of the day, and another 20 minutes to round up a pair of slot-size redfish. We had originally planned to cast soft-plastic jerkbaits for our quarry, but with visibility dulled in the 2-foot depths just beyond the edge of the bloom, our skipper switched to cut ladyfish and mullet. “The snook and reds may not see these baits,” he explained, “but I guarantee they’ll smell ’em. Oily baitfish work best. Their scent really carries in the current.”

Stormy Weather Fishing

Like Kane, many inshore skippers these days are increasingly dealing with murky, clouded or discolored water due to storm runoff, silt and algae blooms, or even sustained high winds can cloud the shallows. In areas like South Florida, the inside passages of North Carolina, Texas and Louisiana marshlands, and New York’s South Shore and Long Island, making adjustments due to water clarity has become standard practice.

“Often, you can run from a red tide,” Kane says. “The blooms along Florida’s west coast are generally splotchy, so you seek out areas where it’s less intense. Whether dealing with blooms or discolored water due to runoff or wind, keying on a predator’s sense of smell is a good idea.”

When water gets cloudy, Kane searches out inlet mouths, where incoming tides bring increased visibility. Scouting for shallow water edged by deeper channels is another good option. “The less depth, the greater the light penetration,” he explains. “Plus, redfish and snook like to hold against sandy-shoal edges that host oyster bars and allow a quick escape to deeper channels.”

Fishing the Different Seasons

Capt. Joey Leggio patrols Long Island and New York’s western South Shore, where a brown-and-rust tide poses a frequent challenge during summer, and silty waters are the rule after a hard, onshore blow. Like Kane, he relies on scent to draw strikes when visibility is poor.

Leggio, who charters out of East Rockaway Inlet, explains: “You need to prepare for multiple scenarios before heading out. I was in a striped bass tournament a couple of years ago, and couldn’t buy a bite in the heavily silted waters courtesy of strong winds the previous night. I switched from bunker spoons to soaking bunker chunks on the bottom and won the contest with a 27-pounder.”

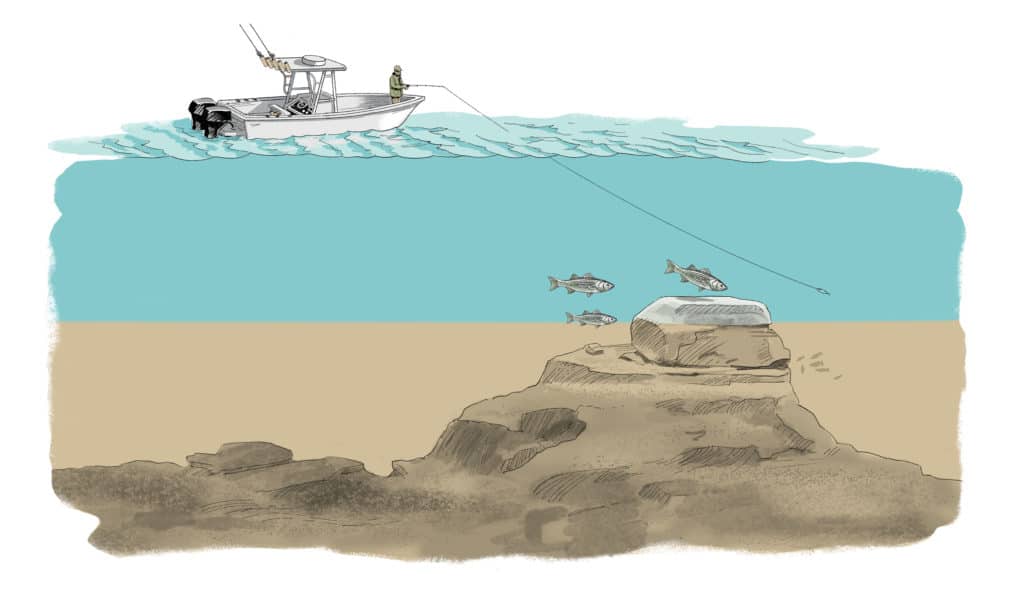

Another point to keep in mind is that silt and blooms don’t always extend through the entire water column. “The brown tide in our bays sometimes reaches only a few feet below the surface. That means you can work your bait or lures beneath it,” Leggio says. “On the other hand, when storms kick up silt on our offshore blackfish grounds, you might be able to find a high place that rises above the worst turbidity and keep on catching. I took a double-digit tautog recently in murky water from atop a rubble pile that rose 20 feet from the bottom in 60-foot depths. Never had a bite at the deeper level. I’m guessing the silt had begun to settle from top to bottom.”

Bright and Loud Color Lures

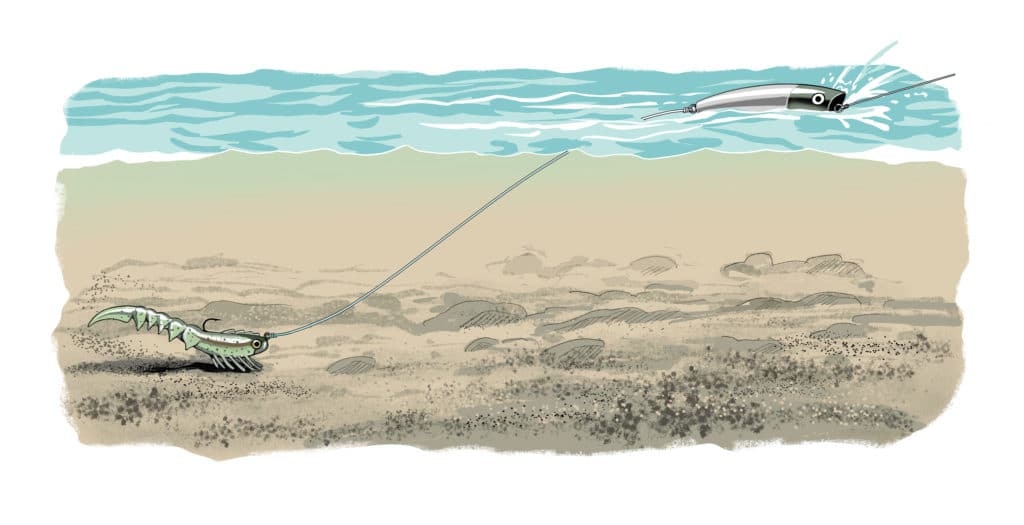

Capt. Gary Dubiel of Speck Fever Guide Service in Oriental, North Carolina, agrees that making adjustments is the key. “We fish for reds, speckled trout and the occasional striped bass in the Neuse River and Pamlico Sound,” he says. “When it rains hard, runoff pushes down the river. Then, we switch to bright colors, more scent, and lures with vibration or surface splash.”

In low-visibility conditions, Dubiel throws white, chartreuse or hot-pink lures. With soft-plastics in moderate turbidity, he prefers paddle tails, believing their vibration helps predators zero in. Still, popping corks are his No. 1 choice whenever water clarity becomes an issue. Keep in mind, he adds, that fishing around baitfish schools usually brings an advantage.

“A small flip or lone jumping mullet will reveal a pod of baitfish obscured by off-color water. Side-imaging sonar is a big help in these situations,” he says. “A cloud of baitfish that suddenly rises toward the surface, then quickly settles back toward the bottom is another good sign. It’s like the bait’s response to predators on the hunt or lurking nearby.”

Texas redfish sharpie Guillermo Gonzalez prefers darker patterns when working marshes, especially when he breaks out his fly rod.

“Get in tight enough that you can see reds crawling across the bottom in a few inches of water, and throw a black or purple Redfish Toad to imitate crabs, shrimp or baitfish,” he suggests. “I favor dark colors so I can spot my fly as I bring it past the fish. I want to put it right in front of them when visibility is limited. They’ll use their lateral lines and other senses to find the pattern if I get it on the mark, but I need to see it to ensure a perfect presentation.”

Read Next: How to Fish the Tides

Capture the Advantage

Off-color water, while generally viewed by most as something to avoid, can also work in the angler’s favor sometimes. In fact, Capt. Bobbi Brady of Florida Saltwater Flats Fishing Charters in Steinhatchee, Florida, welcomes it. She enjoys targeting big seatrout when visibility is near zero.

“The bigger storms flush stained water down the Steinhatchee River and onto the flats of Deadman Bay,” she explains. “And I recently discovered that, while small seatrout avoid discolored water, the lunkers seem to relish it. Just last week I worked a dark, tannic stretch, and drilled trout in the 26- to 27-inch class on scented, root-beer-colored soft-plastics embedded with 1/4-inch rattles, and suspending swimmers touched up with shrimp-scented Pro-Cure Super Gel Fish Attractant.

“With the opportunity to connect with big fish like those, I’ve grown considerably more willing to welcome heavy rains and gusty winds every now and then.”