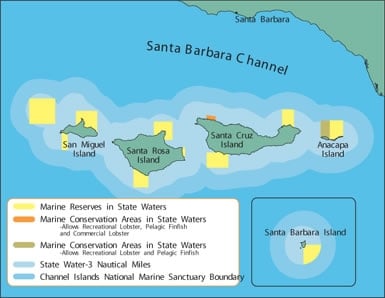

| The much-publicized Channel Islands MPA complex, established last year, closed 175 square miles of ocean to fishing. More no-fishing zones were in the works before California’s financial woes and its new governor put a temporary stop to the plan. |

California’s huge budget crisis, while causing the state’s credit rating to plummet to near-junk-bond status, proved to be an unexpected ally of sport fishing interests when a new administration under Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger announced that a process to create no-fishing zones along up to 20 percent of California’s 1,100-mile coastline was being put on “indefinite hold” due to a lack of state personnel and funding. Some observers had warned that the controversial plan could be a forerunner and model for banning recreational fishing in large areas along the entire U.S. coastline.

The plan to ban fishing via a vast, state-mandated network of coastal Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) was born out of the Marine Life Protection Act (MLPA), passed in 1999 by the California legislature and signed by then-governor Gray Davis. Under the plan, the State Fish & Game Commission (FGC) was tasked with developing MPAs along the entire coast. The Commission, in turn, directed the State Department of Fish & Game (DFG) to facilitate a series of statewide meetings to map out and propose specific MPA locations and regulations.

The first round of meetings to formulate the MLPA plan virtually excluded sport fishing groups, individual anglers, commercial fishermen, harbormasters, marina operators and other user groups from what soon became a “backroom discussion among eco-scientists only – a process funded and pushed by a coalition of protectionist advocates fueled by emotions,” according to Tom Raftican, president of United Anglers of Southern California, an organization of 60,000 independent and club-affiliated sport fishermen. “When the scope of the MLPA plan was made known – including the plan’s extreme posture against fishing, plus the vastness of the no-fishing tracts proposed in maps – a huge outcry caused the DFG to scrap the maps and start (the meeting process) all over again,” says Raftican, “this time with everyone involved.”

The establishment of no-fishing zones in the Channel Islands was to be the first step in a coastwide series of marine-protected areas where all forms of fishing would be prohibited. Fortunately for California anglers, a lack of funding has put that plan on hold.|

Ecos Vs. Anglers

“Ironically, it was sport fishermen who first asked the legislature to look at improving management of 62 existing (pre-MLPA) marine reserves,” Raftican explains, “but the eco-activists jumped in, waving a banner of ‘no fishing, period.’ At that point, the movement took on a life of its own. The lesson here is that what got out of hand in California can happen in any state. Twenty-five years ago, hunters became the targets of activists; now it’s recreational fishermen.”

When the MLPA input meetings resumed, they included “stakeholders,” especially members of the sport fishing community, according to Rich Holland, longtime salt water editor for the 240,000-reader-strong Western Outdoor News, based in San Clemente, California. Responding to angler protest, the legislature granted the DFG an extension, until January 1, 2005, to oversee the meetings and finalize the overall MLPA plan. The DFG was proceeding on that course when funding ran out in spring of 2003, adds Holland. The meetings were quietly suspended until, in January 2004, the DFG drew media attention by sending letters to MLPA “interested parties,” saying “the department has decided to place the process on permanent hold and disband the regional working groups.”

Tom Raftican, right, president of United Anglers of Southern California, met with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to discuss anglers’ concerns about marine protected areas in state waters.|

Before an ever-growing anti-fishing movement ran up against the state’s financial roadblock, however, recreational and commercial fishermen did see California’s first grouping of MPAs created independently of the larger MLPA movement. Pushed by a group called the Marine Reserves Working Group, these no-fishing areas became effective in April 2003. A dozen large underwater tracts, made up of two “conservation areas” and ten zones banning all types of fishing, now apply to 19 percent of state waters surrounding Southern California’s popular Channel Islands, off the Santa Barbara County coast. The ten “no-take” zones involve five islands – Anacapa, Santa Cruz, San Miguel, Santa Rosa and Santa Barbara – and comprise 175 square miles, making the Channel Islands group one of the largest no-fishing complexes in the country and the single largest on the West Coast.

“Considering the potential damage (to sport fishing) had the MLPA movement not been halted because the state ran out of money, we’re lucky to have escaped with just the Channel Islands fishing closures in place,” says UASC’s Raftican.

No-Fishing Zones Unwarranted

Bob Fletcher, president of the Sportfishing Association of California (SAC), which represents most charter and open-party fishing boats in Southern California, agrees with Raftican that the islands’ no-fishing closures weren’t justified. He feels they were driven by environmental activists headed by groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Ocean Conservancy.

“Unfortunately, the Channel Islands no-fishing zones and the larger and parallel MLPA plan were both ill-conceived and based on emotion rather than good science,” says Fletcher. “While advocates of MPAs alleged that traditional fisheries management had failed, the reality was that ocean temperatures had warmed, pushing many fish stocks out of their usual habitats. It was true that some rockfish stocks had declined, but a return to a colder ocean in the late 1990s triggered successful spawning, and recoveries of most rockfish stocks are well underway today. Those areas comprising the potential 20-percent closing of state-regulated waters all along the coast (within three miles of shore and islands) would, in truth, have made up 60 to 70 percent of our popular, prime fishing grounds.”

Bob Fletcher, president of the Sportfishing Association of California, says the creation of MPAs in the Channel Islands was the result of environmental activism rather than sound science.|

Also in January of this year, DFG staffing and spending cutbacks were underscored by Acting DFG Director Sonke Mastrup. The DFG estimated that $1.5 million – which the DFG doesn’t have – would be needed to continue the regional meetings. “Since placing the (MLPA) process on hold, the Marine Region (division of the DFG) has lost 35 positions (a 15-percent reduction in staffing, including law enforcement), and has given budget-driven layoff notices to an additional 22 individuals,” Mastrup said.

Anglers Sold Out

When the MLPA was passed in 1999, then-governor Davis put his signature to the bill, saying, “(this) action will allow all Californians to enjoy this diverse wildlife area, while restoring and preserving marine populations for future generations.” Apparently, when Davis said “all Californians,” he wasn’t thinking of the state’s estimated 1.5 million anglers who fish in salt water, says SAC president Fletcher. A former DFG deputy director familiar with politics, Fletcher strongly disagrees with Davis’s stated motive for signing the MLPA into law.

“I could see how he was maneuvering to capture the environmental vote for reelection in 2002,” Fletcher says. “One of the most driving, no-fishing forces behind the MLPA movement was, and still is, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). So Davis appoints Mary Nichols, who was Western Regional Legal Representative for NRDC, to a cabinet post, as State Secretary of Resources. Then he appoints a new DFG Director, Bob Hight, a man with no experience working for the Department (of Fish & Game).”

Fletcher and Raftican think Davis “sold out” the sport fishing community and traditional scientists who use an array of scientific tools – not just blanket closures – to manage marine resources. “These traditional tools include closed seasons, quotas, bag limits, size limits, gear restrictions, depth limits, protected species – all the different ways to manage fish,” Fletcher says. “Davis orchestrated the (Fish & Game) Commission vote to create the Channel Islands MPAs and help his own reelection. And just as bad, the whole MLPA looked to outside interests – special interests – to fund those workshop meetings held during those two years to formulate the originally proposed MLPA plan. So the NRDC, who we’re squared off against to keep our fishing areas open, becomes the chief funding source for meetings closing us out, and attracts other no-fishing groups to join the fray.”

Davis won reelection in 2002, but fortunately for sport fishing interests, says Fletcher, his dismal political record led to an unprecedented recall election in 2003, in which he lost decisively to Arnold Schwarzenegger. That change pleases both Fletcher and Tom Raftican.

Arnold to the Rescue

Angler groups feel commercial trawlers such as this damage the marine environment through heavy amounts of bycatch and by destroying bottom habitat.|

“Governor Schwarzenegger launched a more objective approach to the issues,” says Raftican. “He replaced Nichols, as Resources Secretary, with Mike Chrisman, a former Fish & Game Commissioner and the only one of five Commissioners to vote against the Channel Islands MPAs. And he appointed Ryan Broddrick as the new Director of Fish & Game. Ryan is a fisherman and hunter.” Broddrick was an up-through-the-ranks DFG employee for 20 years, prior to his directorship appointment, according to DFG sources.

The state’s budget woes and resulting suspension of the MPA plan came as a relief to individuals and groups opposing the fishing bans. Losing 20 percent of the state’s ocean fishing areas would lock out anglers from hundreds of square miles of productive grounds, says Raftican. “The halt to the plan gives (the sport fishing community) a chance to regroup and refocus the current administration’s analyses of California’s fisheries,” says Raftican. “There’s not enough regulation on bottom trawling, for example. Not only does trawling account for a disproportionate number of rockfish caught, it also kills a lot of bycatch (non-targeted, discarded species) and destroys bottom habitat.”

Fletcher says that a perceived-to-be-depleted bocaccio (salmon grouper) population supposedly concerned no-fishing activists, but the fact is that the DFG hadn’t conducted a Southern California bocaccio survey since 1977 – until last year, when the DFG took hook-and-line samplings on selected party boats.

“Those trips found a lot more bocaccio and other rockfish than expected,” says Fletcher. “Everywhere they went they caught bocaccio, in lots of different year-classes too.”

For 22 years, Fletcher says, depressed rockfish catches were caused by warm ocean temperatures, not overfishing. From 1976 to 1998, California waters were warmer than normal, he says. Now the thermographic pendulum has swung the other way, and the water is colder than normal.

“Warm water’s great for bringing up tuna and dorado from Mexico,” Fletcher explains, “but it doesn’t do much good for plankton production, smaller marine animals, rockfish populations and kelp growth. In the past five years, with colder water, ever-larger year classes of rockfish are being found by Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) surveys in central and northern waters, and for some species that’s in record numbers.”

Raftican is concerned, however, that with state funding totally expended, “the MPAs and no-fishing movement will again be infused and influenced with money from extreme environmental groups.”

Raftican says the state should be looking at the concept of creating “ocean parks,” which UASC supports, not blanket no-fishing zones. “The parks would have high recreational value. They would be areas where sport fishing is allowed, but where destructive practices like bottom trawling, longlining and gillnetting are prohibited.”

Indeed, as this article was written, the NRDC was urging supporters to push ahead with the no-fishing zones and tell Governor Schwarzenegger “to ensure that this landmark law (MLPA) is put into action.” A sample letter to the governor, offered on the NRDC website (www.nrdcaction.org) says, in part, “Your administration has stated that it is committed to environmental protection and public input, yet the decision by your Department of Fish & Game to delay the MLPA indefinitely is in direct contrast to that commitment (and) the new marine reserves in the Channel Islands are a good first step towards better ocean management in California, but they are only a first step. We must follow through by keeping the MLPA alive.”

At the same time, a coalition of environmental groups was seeking private funding to bail out the MLPA movement, including a reported $800,000 from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Another organization offering funds was the Ocean Conservancy. Warner Chabot, vice president of the Ocean Conservancy, believes the new California administration should streamline, not sideline, state marine-reserves law. “Postponing the creation of marine reserves allows further decline of living ocean ecosystems and only makes it harder to restore ocean health and diversity,” says Chabot.

Ocean Conservancy sources also say environmental leaders understand the budget and staff limits at the California Department of Fish & Game, and have offered to work with the state to get additional foundation funding to implement this law.

Even with the push for more no-fishing areas on what appears to be at least temporary hold, “the battle is anything but over,” says SAC president Fletcher. “This is going to be a long, long process. Fishing in California has become a politically driven activity and sport fishing interests all over the country should take notice. Some people think, as California goes, so goes the rest of the coast.”