[Be sure to click through all the images in the gallery above.]

Before you read on, I first want to remark that I fully realize that what I’m about to say next could be considered a total cliché. But damn it — there really is something to be said about washing down conch fritters with cold Kaliks while watching a Bahamian sun fall after a day of bonefishing. By and large, fly-fishermen take pleasures in simple things. We are drawn to tradition, and with any lasting tradition a foundation based on authenticity can be found. Each island in the Bahamian chain has its own unique charm, but that classic island vibe that we’ve all come to love has become harder to come by. For those who do want to cap off an outstanding fishing day with a French-inspired hors d’oeuvre platter and an aged merlot, the good news is that the Bahamas have plenty of great options. But even better — for those of us who crave that old-school ambience, the small island of Water Cay located off the east side of Grand Bahama’s horn offers that and much more.

The topic of Bahamian authenticity came up in a conversation with Angling Destinations’ Scott Heywood. Though Heywood’s job entails selling customers on particular destinations, I could tell by the way he spoke about Water Cay that this was no sales pitch. He genuinely felt that the fishery is strong, the guides exceptional, and the spot — a true Bahamian experience. Heywood went on to say that he and other Angling Destinations personnel had explored these waters and found great success in years past. The problem had always been that, despite not being far from the mainland’s coast, it was relatively hard to reach. For a time, the Water Cay Bonefish Lodge was open for business, but eventually it failed. The hurricane season of 2004 pounded the lodge and left it crippled and empty of staff, and therefore guests. However, after three years of sweat equity, the lodge opened for business once again, and Sidney Thomas became the head guide and had the early task of bringing on two more hardworking bonefish experts.

Keeping it in the family, Sidney hired his brother Ezra. Born on Abaco, both Thomas boys entered the world with an innate sense of fishing. Together, they opted to call on another Abaconian, their friend Greg Rolle, who shared this trait, to round out the guide staff of the new and improved Water Cay Bonefish Lodge.

Bahamian Bushwhacking

A few weeks later, I found myself awaiting my bags in the Freeport airport. In between numbing stares at the slow-moving luggage belt, I scanned the room for a person who fit the guide profile. When I looked outside, I noticed a tall, stoutly built Bahamian fellow peering in through the glass as though he was looking for someone. The scruffy-faced man wore a sweat- and salt-stained, tan beanie that lazily sagged from the weight of the hair tendrils stuffed inside. He was, in my book, textbook Bahamian. I crossed my fingers in hope he was my ride. Finally, my rod tube came down the belt. Grabbing it must have given away who I was because the man who was curiously looking inside moments ago was now standing in front of me with an outreached hand and presenting himself as Ezra Thomas. I followed him outside, where he introduced me to Doug Jeffries and Mike Kotrick. In lieu of staying at Water Cay Lodge, Angling Destinations arranged for the three of us to use a catamaran live-aboard as a bonefishing base camp for the next week. This would enable us to be close to the fishing and also allow for mobility depending on the tides. By the time how-do-you-do’s and where-are-you-from’s were complete, Ezra had already veered the van off the paved highway, and we were bouncing down dirt roads leading us farther into the Bahamian bush.

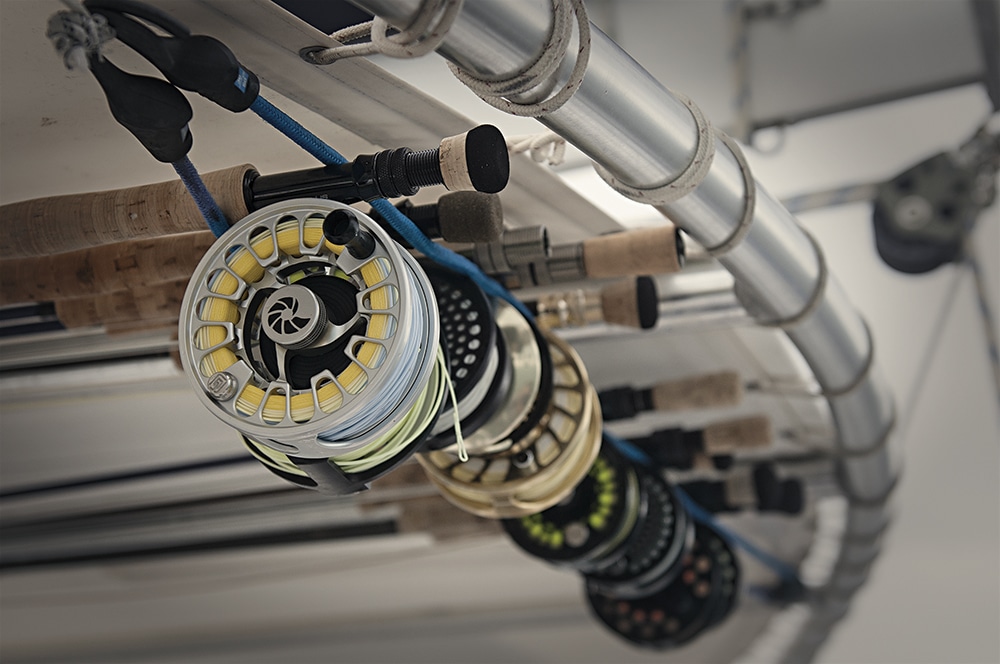

Deep in the woods, Ezra stopped the van at an inconspicuous ramp where his brother Sidney waited to taxi us to our floating home. When we arrived on the boat, our bags had been stowed in private cabins and flip-flops retired below deck. While rigging rods and tying leaders that evening, Doug, who had fished with the Water Cay boys on numerous occasions, described the guides we’d be fishing with for the next few days. His description matched Scott Heywood’s to a tee. Extremely hardworking, driven to catch fish and, most importantly, unbelievable teachers were terms he unknowingly repeated over and over.

Morning finally arrived, and right as we were finishing up breakfast, Sidney and Ezra began pulling their skiffs away from the guide quarters, a lobster boat anchored a few hundred yards away that would be left in Greg’s hands for the day. Doug and I piled in with Ezra, and Mike went solo with Sidney. It was a short run to the first flat, and moments later the only sound in the air was the soft entry of Ezra’s push pole into the shallow water.

“Fish moving away from that point” were the first words out of Ezra’s mouth after he killed the engine. He gave the skiff a shove that spun the boat in a way that gave Doug a favorable casting angle. On his second false cast, Ezra gave a calm yet authoritative instruction: “Let it fall.” When the small pattern hit the skinny water, the fish surged in the opposite direction.

Ezra sternly commanded, “Leave it — let it sit!”

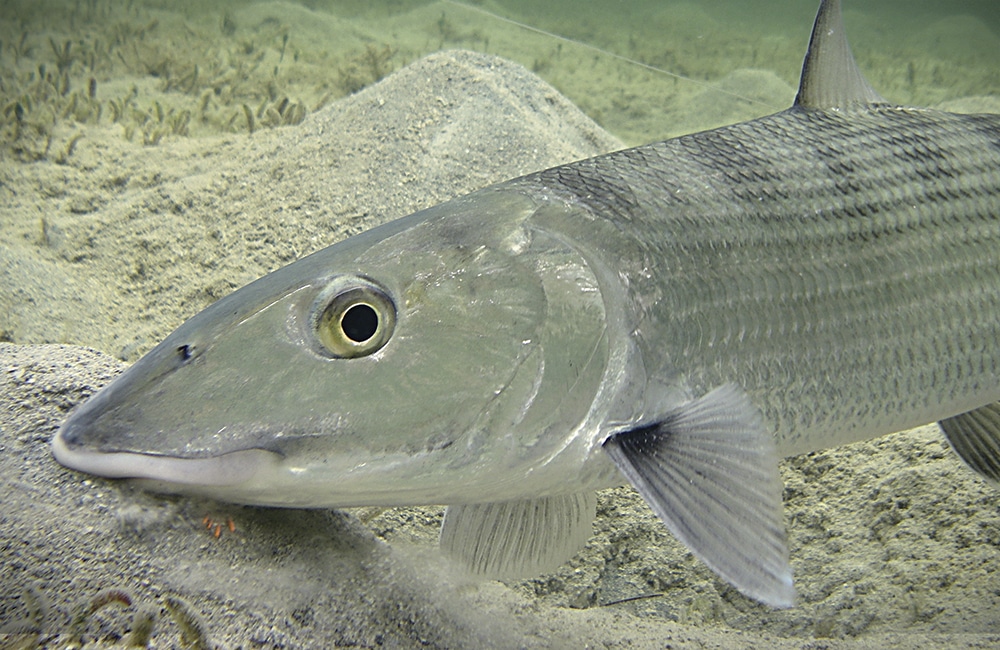

I found this odd — the fish was briskly swimming away from the fly. Like a hound on point, Doug stared at the fly and diligently did as he was told. Once the fly settled, so did the fish. Standing behind Doug, I was certain a second cast was coming, but it never came — a follow-up presentation wasn’t needed. After a couple of seconds, the fish did a 180 and swam with purpose toward Doug’s stationary fly. When it got close, the bone warily stopped.

“Short, slow strip,” Ezra requested. As Doug’s left hand moved back, the fly inched toward him and switched the fish into high gear. “Drop it!” Ezra said.

By dropping the fly, Doug forced the charging fish to slam on the brakes so hard that it nearly went tail over head when it ate the fly. “Long, slow strip!” Ezra remarked in a raised voice. When Doug reached the back end of his strip, he raised his rod and the tip bounced erratically as his fly line leapt up from the deck.

As he fought the fish, Doug smiled and said, “Interesting method, isn’t it? It took me years, but if you can discipline yourself to simply wait like they say, you’ll catch twice as many fish. Isn’t that right, Ezra?” Ezra cracked a smile and added, “I always have my clients make the cast and wait, no matter where the fly falls. Bonefish are curious, and even if a fish spooks, it will more often than not come back to look for what it was that scared him. Waiting is the hardest part.”

For the balance of the day, Doug and I traded shots, and while Doug had the technique dialed in, my stripping hand was still a little trigger-happy. After each failed attempt, Ezra followed with a specific reason for why the fish didn’t eat. Toward the end of the day, slowly but surely, the jones to strip or pick up and recast diminished and I too was finding success in patience. Even when I did something right, the hookup would follow with a lesson from atop the poling platform.

The following day started much like the previous had, except I was on my own with Sidney. It was windy, so Sidney steered the skiff to the lee side of the island. As he poled, I told him that after one day I was absolutely blown away by his brother’s technique. With his eyes locked on the sandy flat in front of him, he chuckled and agreed that the technique is different than what a lot of people are used to. “It’s not that Ezra, Greg and I are trying to do something different; it’s just a method that we find to be the most effective.”

Just like his brother was the day before, Sidney was on fish almost immediately. And also like his brother, he followed each screwup and success with a logical reason for why the fish ate or didn’t eat. As the day wore on and my mental endurance grew, I noticed that the eat ratio on the fish I threw to was higher, a credit that I freely give to the men pushing the boat. Their fish-spotting skills and boat-handling abilities were unbelievable, and they certainly knew where the fish were. But, most importantly, their methods were causing me to think the way they thought.

Sidney and I found a nice flat next to a deep channel and he began poling. I laid up singles and doubles and received high fastball opportunities in return. When we reached the deeper water, Sidney mentioned a nearby flat that we could wade, and I was all for it. We anchored the boat and sneaked to the outside of a creek mouth. Along the way, we didn’t see much, and when we reached the mouth, I couldn’t help but think, “Why this one?” It looked like dozens of others I’d seen along the way. Sidney said, “Let’s just stop here for a while; they are going to come out of the mangroves as the tide falls.” We stood there in silence and heard an unmistakable slurping feed. “See, the tide is falling — they are getting nervous about finding their next meal. Just give it a little more time; pretty soon there won’t be enough water in the creek and they will come to us.” A few minutes later, a pair slowly cruised out of the mouth but were just out of range. Then, another and another and another. As the water dropped, the time between bonefish sightings dwindled into nothing. Pretty soon, there were so many tails, backs and wakes of bones it seemed as though someone had lifted the edge of the creek like that of a kiddie pool, pouring water and fish toward us — as the water rushed out, so did the fish. It was one of those moments when I didn’t know what fish to cast to.

Sidney’s skiff was now about 200 yards away and it was getting dark. “Stay here and enjoy the rest of the tide. When I make it to the boat, start heading my way,” he said. For the next 30 minutes or so, I was left on my own, and after managing a few more fish, I noticed Sidney was in the skiff. About five steps into my walk, out of nowhere I felt a hard thump at my feet and looked down to see a five-foot lemon shark with its jaws latched onto my heel. (OK, maybe it was only three feet long, but just like the camera adds 10 pounds, a shark between your legs appears longer.) Freaked out, I high-stepped it across the flat, but the shark was still in pursuit. I swatted at it with my rod tip, threw handfuls of sand at it, kicked the water, but it wouldn’t leave me alone. I looked up and expected to see Sidney on his way to the rescue, but when my eyes found him, his head was pointed at the sky, his mouth agape, and all I heard was hysterical laughter. When I finally made it back to the boat, he was still laughing. He caught his breath and remarked, “Welcome to Water Cay.” Only a true Bahamian could find humor in a paleface American running scared from a baby shark.

Admirations

On each successive day, without fail, aside from excellent fishing, something out of the ordinary happened. Being attacked by the little shark and outrunning a lightning storm were two instances that stick out, but there were other events that didn’t cause the heart rate to increase in a bad way. There was one afternoon when we came across a cluster of about 50 nurse sharks mating, which was something I’d never seen before, and there was the evening that I hooked a tarpon on a Crazy Charlie bonefish fly — that was also a first. Looking back, all of these events, whether they raised the hair on the back of my neck or simply caused me to stop and admire the natural world, gave the impression that I was in a place that has remained virtually untouched over the years. High-end resorts have their place for sure, but for me, I prefer living a barefoot lifestyle. So much so, when we returned to the mainland, I realized I had left my flip-flops stowed below deck in the cat. As best as I can put it, Water Cay doesn’t offer false promises but rather an authentic old-school Bahamian experience. Heywood was right: After fishing with Sidney, Ezra and Greg, you will be a better bonefisherman. With the three of them, the teaching never stops, which tells me that, while they are all masters of their craft, they continue to take their guiding to the next level.

Water Cay Style

Clients learn to think how Sidney and Ezra Thomas and Greg Rolle think, thanks to their style of guiding. These guides are easily able to put wind, time of year, past weather conditions, current weather conditions, tide and moon phase together to come up with a game plan that matches their clients’ desires and skill levels. I’d known about the concept of “strip, drop, short-strip, wait,” but I’d never seen it physically displayed until fishing at Water Cay.

Before you go, remember that the basic rules for success are this: Cast, let it settle, and see how the fish reacts. If it doesn’t look interested, give the fly a short strip and continue to do so until you get a reaction. When you do get a favorable reaction, stop stripping and let the fly drop. The goal is to get the fish to make a beeline for your fly, and then you stop it, forcing the fish to think it’s going to overrun it. Anglers have to be disciplined to fish this way. Done correctly, the fish panics when it thinks it swam over its next meal and eats out of desperation.

Getting There

Sidney and Ezra Thomas and Greg Rolle are about as hard-core as you can get. They don’t take clients on a loop and they definitely don’t punch a time clock — they go where the fish are going to be, no matter how far the run or how much poling it takes to get there. They are among the hardest-working guides I’ve ever fished with.

That being said, Water Cay Bonefish Lodge and its primary booking agent, Angling Destinations, are willing and able to customize a trip for you. Whether you want to stay at the lodge, arrange for a mothership, camp, fish from a boat or wade, all parties involved want you to have a trip of a lifetime.