If you know me, you likely know that in addition to owning a charter fishing business, I’ve dedicated a significant portion of my life to the conservation of marine resources. I’m going to admit right now that it’s self-serving. It’s always been my view that conservation-focused management (such as keeping a few fish in the water) is way more important than how many I can kill. Because it’s not really the killing that drives business, it’s the opportunity to catch.

But the intrinsic value of marine life has never escaped me, and it’s really why I got into this line of work in the first place. Yeah, that includes whales. I mean, especially whales! When one lunges to the surface feeding just 60 feet from the boat, jaws drop. No matter how many times I see stuff like that, mine still does too.

Why Are Right Whales Declining?

I’m not blind to the right whale’s plight. And I’m not okay with the very real possibility of an extinction event if we don’t figure something out. But I’m also not okay with going out of business.

Like just about every other whale species, right whale populations were nearly wiped out by whalers in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. In the 80s and 90s they seemed to be on their way back, reproducing well, and numbers appeared to be steadily increasing. Then, they weren’t. The question is why?

Unlike other whale species there’s been a precipitous, seemingly irreversible decline since 2000. Today, it’s estimated that there are less than 350 individuals left. Meanwhile you’d have to be blind to not see that humpbacks, fin whales, and others seem to be increasing in numbers. Seriously, we see more and more of them every year, not just offshore but inshore as well.

Right whales are filter-feeders and eat the small stuff (such as krill) instead of prolific menhaden and sand eels that humpbacks and fin whales consume. Climate change and resulting shifts in that sort of forage are likely part of the equation, but there’s certainly mortality coming from entanglement in fishing gear and ship strikes.

Boats Hit Right Whales

I’m not going to lie. There’s no getting around it. Boats, particularly the long-range go-fast types, do hit whales. It doesn’t happen frequently, but well, I wouldn’t say it’s rare anymore either. That’s simply because there are a lot more whales around (humpbacks and fin whales). In the two and a half decades I’ve been doing this, I’ve never even seen a right whale.

Still, NOAA is able to point to a specific number of right whale vessel strikes. Unsurprisingly, it’s not that many — I think 12 since 2008 — but when you consider that there are only around 100 mature females left, every single death is significant, and arguably catastrophic. Of course, there are likely more strikes that aren’t documented, and you have to add commercial gear entanglements into the equation too. When you consider that those females give birth only once every three to ten years, the math doesn’t look good.

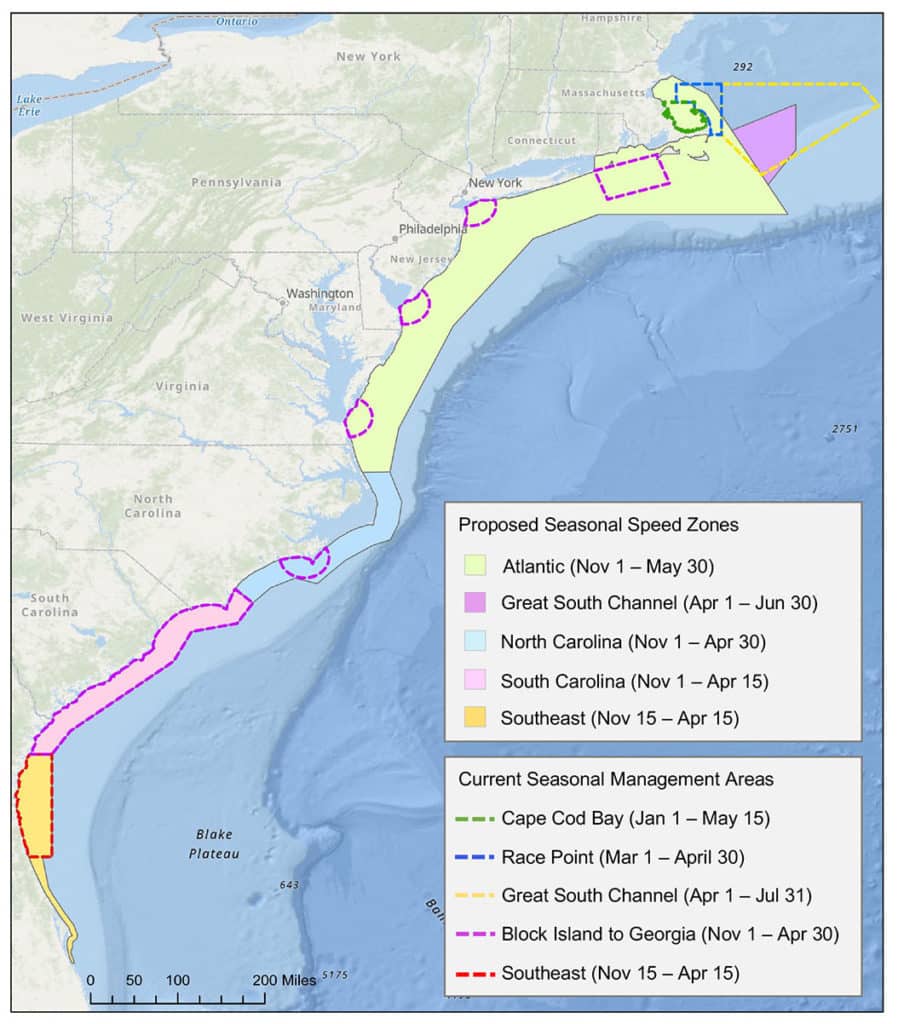

NOAA Fisheries initially responded to the decline in 2008, by putting in place 10-knot speed limits for vessels 65 feet and over in those times and areas where scientists determined interactions were likely to occur. They include Cape Cod Bay, Race Point and the Great South Channel, an area from Block Island to Montauk, and all the Mid-Atlantic ports, as well as a good piece of real estate along the beach from southern North Carolina to northern Florida (which is apparently a major calving area).

Absolutely, this jammed up party boats in particular, plus the shipping industry sure wasn’t happy about that rule. Yet the recreational fishing community was largely mute because it didn’t include most recreational and charter folks.

Clearly, those measures did not significantly stem the decline. Some environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) sued and more-or-less forced NOAA into putting out a proposed rule last July that downsized the vessel length to 35 feet, but also greatly expanded the area and times of the slow speed zones. The zones now take up much of the east coast out to 100 miles during some important fishing times of the year (see chart).

Proposed Regulations Hurt Anglers in Large Boats

What does that mean? Well, for me, it means that in May (one of my busiest months), I can’t get my 36-foot Contender on plane once I get out of the inlet. So, it’ll take me 6 to 8 hours and a LOT of fuel to get on a tuna bite. And if I simply wanted to run from Jones Inlet to Breezy Point to take my guys striper fishing? I figure that’s about a two-hour ride now.

Ridiculous man. No one is going to pay to do that. Losing that entire month of May would hurt pretty bad. And then I’ll have to eat it again November and December?

Yeah, July to October, I can open her up, and turn and burn. But what folks need to understand about the charter business is that to make it work, you need every month. You can’t just peel off a few months here and there and expect to stay in business. Yeah, I’ve got other smaller boats which other captains run for me, but I need to have all of them running, and you can’t tell me that my massive investment in the 36-footer is worthless now.

Forget about me for a minute though, cause I’m just one guy along a big coast. There are entire fleets that can and likely will get hurt badly by this rule if it does go into place. And then there’s all those dockside businesses that service all that traffic.

And for what? From NOAA’s own data, the chance of a vessel hitting a right whale, considering the volume of boat traffic in the proposed zones, is about one in a million. And if we’re just talking about one 36-foot Contender? I’d have a better chance of getting struck by lightning, or perhaps winning the lottery. I get that we need to try everything we can to prevent an iconic species from becoming extinct, but it certainly appears to me that we’re talking about eliminating entire fisheries because of a very slim chance one of us might hit a right whale.

This is such a gigantic area, how are they possibly going to enforce an open-ocean speed restriction on this scale? I’m fairly certain compliance is going to be lacking. With that in mind, can anyone say with a straight face this sort of thing might actually help the right whale’s situation?

Right Whales Are Easy Targets

Let’s get back to why other whale species are growing in population while right whales are in major decline.

I hate to say this, but right whales are dumb animals. It’s not their fault. It’s not anyone’s fault. But that doesn’t make it untrue. I mean, they were the “right” whale to kill, partly because they were so docile and didn’t move when they were approached. (Well, also because they immediately went belly up and floated when stuck with a harpoon.) Plus, they spend almost all their time on the surface skimming copepods. And lastly, they give birth way less than say humpbacks.

The point is that some of those characteristics that made them the “right whale” back in the whaling days, makes them ill-equipped to survive today no matter what speed rules we put in place. And that sucks. Perhaps there’s something we can do about that, perhaps there isn’t.

But are we really willing to sacrifice an entire industry? Especially one that works so hard to support healthy oceans?

I know I sound like a complete jerk when I say this, but at some point, you must admit — if a species can’t successfully interact with human beings in this day and age, then maybe we just have to let natural selection take its course. Because what’s next if this doesn’t work? Shut down all marine traffic? How far are we willing to go?

We Need A Better Solution to Save Right Whales

I’m not suggesting we don’t move forward with some sort of well thought-out, practical solution that helps to avoid potential ship strikes without needlessly putting a lot of folks out of business. For now, NOAA Fisheries needs to pause action on the proposed rule until the agency has had the opportunity to further engage with stakeholders. There was virtually no engagement with anglers prior to this proposed rule being put out there. I’m certain there are more strategic and practical solutions that could help the fleet avoid potential ship strikes without keeping everyone tied to the dock.

All said, I understand fully that my judgment may be clouded here — my livelihood is kind of at stake. And honestly, this is a tough topic to navigate without coming across as the self-interested hypocrite. To think about this objectively for a minute before I inevitably get pulled back into back to fight-or-flight mode, you can really boil it down to two conflicting ethical propositions:

- Is it okay to drive an animal to extinction in the name of business? What some would describe as greed?

- Or is it ethically wrong to put in place measures that put people out of work, when there’s an extraordinary amount of doubt to whether such measures will actually accomplish the goal?

While my conscience hurts me a little bit for this, I’m leaning toward the later. I’d like to hear what you guys think.

Editor’s Note: Captain John McMurray is a former Legislative Proxy at the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) and a staunch advocate for managing northeast fisheries for abundance. A former Petty Officer in the Coast Guard, McMurray started a guide business in New York waters back in 2000. He’s well known as a top guide for striped bass and tuna fishing, specializing in run-and-gun tactics with topwater plugs or flies. Check him out at nyctuna.com.