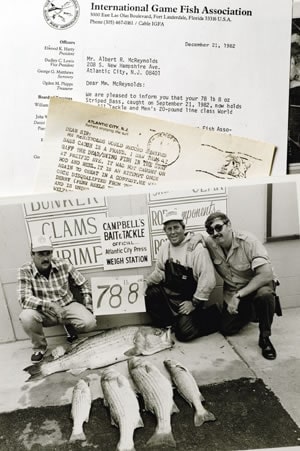

When Albert McReynolds landed what proved to be the world’s largest striped bass ever taken on rod and reel, from a jetty off Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1982, he never imagined how the event would change his life. As we see in Part II of his remarkable story, catching a world-record fish can carry a heavy price indeed. We pick up on the morning after McReynold’s epic battle with the 78-pound striper, at the tackle shop where the fish is being weighed.

It got to be just about almost daylight, the crack of dawn. And the tackle shop is on a road where all the guys are going to work – construction workers, roofers, plumbers, carpenters, guys who work at the casinos and build the casinos in Atlantic City. And people start pulling up when they see this fish hanging on the scale. All of a sudden the Fish & Game people show up, the local TV people, the radio people. It turns into a crowd. Guys are asking, “Who caught the fish? Where’s he at? I want to talk to him.” Guys are lighting cigarettes and putting them in my mouth, pouring Budweisers on my head, drinking beers. It’s turning into a festival.

Now, in order to qualify for an IGFA record, I had to surrender the lure, the rod, the line, the reel – everything. I had to explain the catch, how I handled the fish, how it was hooked and where. Everything in detail. Nobody tells you when you land a world-record fish that there’s going to be an investigation. And this investigation is supposed to be handled very quietly through the IGFA. Nothing’s supposed to be divulged until they reach a decision at the conclusion of their investigation and tell you if the fish qualifies for any world records. You need a lawyer immediately because you shouldn’t open your mouth or tell anybody anything. The press calls it “freedom of press,” but what you’re actually doing is robbing yourself and your family. Because when you divulge everything it becomes public knowledge. The tackle companies feel they don’t have to pay you nothing. And they’re going to get a million dollars’ worth of publicity. What they’re going to do is give you a hat and a T-shirt, and that doesn’t feed your family.

Well, we wound up with everybody there, and the fish is put back on the scale. And this weighmaster guy gets out the record book and he says, “Okay. Cape Cod, Massachusetts, 73 pounds. Caught by a guy named Charlie Church.”

He moves the scale and it goes 71, 72, 73, 74. He says, “You got one record. You beat the 73-pounder what was caught by Charlie Church.” Then he says, “Now this is for all the marbles. Montauk, Glen Cove, Long Island, 76 pounds, the all-tackle world record.” Then he goes, “Seventy-five, 76, 77, 78, 79.” It teeters and balances out. He taps it back. 78, 8. He says, “Albert, to my knowledge you just won everything, and you may have the record for 20-pound test.”

He says to me, this guy who’s the weighmaster, as he’s shaking my hand, “You just won the state record. You beat the Massachusetts record. You beat the New York record. Thank you for bringing this fish to my shop.”

We wound up going back inside his office and signing the proper papers with witnesses and everything. And the phone rings, and the secretary comes over to me. She says, “A man’s calling, says it’s absolutely urgent to speak to you.”

She gives me the phone and this guy comes on. He says, “Albert, you don’t know me. My name is Nelson Bryant. I’m an outdoor sportswriter for the New York Times. I live up here in Martha’s Vineyard.” He says, “Listen, are you sitting down? Sit down for a minute.” I sat down. He says, “I’m in touch with the king of Sweden. I’m trying to reach a man who owns Waterford Crystal in Ireland. There’s a fishing contest on.

A lot of people don’t know about it. We’re trying to track it down and find out how to qualify for it or how to file for it, or get an application, or find out what the rules are. You just might have won a whole load of money. You stay there now. I’m gonna call you back as soon as I hear something.”

After that I walk outside, and here comes my wife through the crowd. She says, “What’s going on?”

I tell her, “I caught that fish.” And I’m pointing to the fish.

She says, “Wait a minute. You gotta be to work pretty soon. We need the money ’cause it’s going to be a long winter.”

I say, “I just got off the phone with a guy who told me I might’ve won a lot of money or something here.”

She says, “Yeah, I’ll believe it when I see the check. How long is all this going to take?”

Soon the weighmaster guy is talking to me again. He tells me he’s gonna take the fish and put it somewhere safe. My rod’s gone, my line, my lure, the tackle and everything I had is gone. Now even the fish is gone. I’m standing there with absolutely nothing, and I’m groggy and tired beyond belief. My feet are still soaking wet and I’m trying to figure out what’s going to happen next.

Then this guy pulls up with a truck advertising this tackle company. They’re one of the biggest companies that make fishing reels. He says, “Congratulations, man. Listen, get the reel and put it in the picture so it goes in the magazines or in the newspapers. Now, I’m gonna authorize right now to you a lifetime supply of fishing tackle. And you’ll probably get cash too. I’ll get back to you.”

Then he gives me a hat and a T-shirt and asks me to put them on for the photos. I say, “Yeah, why not?”

Next thing I know, the secretary comes back out. I’m in the parking lot, posing for pictures with people. She says, “That man’s calling again from the New York Times. Says to get you immediately.”

So I go back inside and pick the phone up. The guy says, “Albert, this is Nelson Bryant again. I got some information for you. Listen to this. There’s a ‘chance of a lifetime’ fishing contest. It’s a bounty. It’s being handled by Lloyd’s of London. The Blair Mail House Nebraska people are handling the applications. We’re having a private courier pick one up and bring it to New York, for you to claim one of the prizes. The contest, from what we understand, awards a prize for breaking the next IGFA world record for four species of fish. Rainbow trout, largemouth bass, king salmon. And what do you think the last one is?”

I say, “Striper?”

He says, “Striped bass. You just won, to our knowledge, $250,000. Me and you, Al, are going to become good friends. I’m going to take the New York Times and point it at their head, like a double-barrel shotgun. And if they don’t give you your money, I’m gonna blow it all over the newspapers. They’re going to send representatives down from the tackle company that’s sponsoring the contest. Now have a good day. I’ll get back to you if anything changes. Just watch yourself. Be careful. You’re dealing with some people that I don’t think you’re used to dealing with.”

After that, the tackle-shop owner tells me if I want any tackle, anything at all, to take whatever I want. Just let him know what I need. He also tells me he has been in touch with an insurance company, since a prize is involved. He’s gonna take care of the fish and insure it for $100,000. He releases this to the news media, tells them he is insuring the fish and that he’ll be holding it for safekeeping.

By now I’m late for work at the Beach Patrol. Dozens of guys offer to give me a ride. When I get to the lifeguard station it’s about 10:30, 11:00. And the chief walks up to me and says, “What are you doing here? Go home. You’re suspended. We’re docking you for the day. You never called. You never showed up.”

As I’m standing there, some of the other lifeguards who want to heckle me are saying, “Wait, you can’t go anywhere. Ted Koppel’s calling. NBC’s calling.” They’re breaking my balls and humiliating me and treating me terrible. My head’s pounding. I’m upset, tired, frustrated. All this stuff is happening and it’s overwhelming. Your feet leave the deck and you’re floating on cloud nine, and the next minute you’re walking into mean, jealous people who want to treat you terrible.

The chief also tells me to have all these phone calls stopped because they’ve been getting over 50 phone calls an hour from people who want to talk to me. Then the assistant chief says, “What is all this bull- over a fish? All it is is a stinking fish. I don’t know what everybody’s getting excited about.”

I walk home on the boardwalk. I finally get back to our little rental apartment. I see the bed and I collapse. I must have passed out. I wanted nothing to eat, nothing to drink. I just wanted to get some rest. I don’t know how long I slept, but my wonderful, beautiful wife, she wakes me up with hot chicken noodle soup and tells me to get up, it’s time to go to work. I must have slept 24 hours.

I get to the lifeguard station, put on my uniform and go down to the beach. Before I know it, I get a call at the station. They tell me that the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute showed up and was examining my fish. And that the people handling the $250,000 contest were in town checking the fish, and wanted to know if I used any of their tackle. Which I didn’t. I didn’t use anything of theirs. But the application for the contest said you didn’t have to use their tackle.

I don’t know how many phone calls I got while I was working on the Beach Patrol the last couple weeks there, but it was unbelievable. I mean, I didn’t have a minute’s peace. There was always somebody who wanted to talk to me, somebody who wanted to meet with me. They wanted me at the Elks, the Moose, the VFW, the American Legion, the fishing clubs. All these so-called new friends wanted a piece of me.

This fellow who’s the weighmaster and is holding my fish, now he wants to see me. He asks me who I would like have mount the fish. I said I’d like to give a local guy a shot. One guy comes to mind, and I tell him to get a hold of him.

So this taxidermist took on the task of making the mount for me, and the agreement we reached was that I was to get a skin mount. And there was supposed to be a right-facing mount and a left-facing mount. And I was assured this would be done.

When the mounts were finished, they were delivered to the weighmaster’s store. I went to see them and there was a right mount, a left mount and a full mount – but they were fiberglass! I asked him where the skin mount was, the original fish, and he says the taxidermist told him it was destroyed. The world-record fish is destroyed! Now I know he has a $100,000 insurance policy on it, but that doesn’t matter in the sense that what I really want is the world-record fish, the only one of its kind in the world, the largest caught on rod and reel. I want that. That’s mine. That’s my trophy, but I never got one.

Eventually the lure company comes forward. They give me a hat, too, tell me I’m on the advisory staff. The deal is they will get a mount of the fish. They will also give me $2,500 and tackle boxes filled with my choice of tackle from their plant.

Then the guy who weighed the fish, insured it and kept it at his store, he’s also asking for a mount to display in his tackle shop. Now here I am, a fisherman all my life and a lifeguard in the summer. I have no education. I can’t read or write. I never took a course in business. I’m really in a mess here, and it’s starting to get worse and turn ugly. But I don’t have any money to pay for an attorney.

Anyway, I get laid off from the Beach Patrol. I’m going to collect unemployment or try to find work in Atlantic City with the teamsters. I work there part-time with guys who I grew up with, who were friends of mine. I’m also a book holder for warehousemen, chauffeurs and truck drivers.

Around this time I start getting hate mail. I think I know who it’s coming from, and we track it. But I refuse to prosecute because it’s a family member. The hate mail says that I am a cheat, a fraud, that the catch is a hoax, a scam, that I devastated the striped bass population by killing the queen bee.

The guy who was with me when I caught the fish, he stops seeing me, talking to me, coming over to visit or going fishing with me. He starts becoming very scarce and evasive when I try to reach him.

Everything starts to go nuts. All kinds of stories are flying around. If I rounded up all the people who said they seen me catch the fish and was with me, they would fill a 70-foot party boat. Guys are telling me they seen me jump on the fish’s back and ride it to shore. They were there. They caught a 69 when I got the 78. Years later, a guy tells my son the story. I walk up and say, “I’m Al McReynolds.”

The guy tells me, “Al McReynolds is dead. He drank himself to death.”

My family and I wind up moving out of Atlantic City, over to the town of Brigantine. We move into a hotel called the Blue Marlin for the winter. I’m trying to find work. It’s getting toward Thanksgiving and I’m still waiting to hear from the IGFA what their decision is. I go up to the Atlantic City Convention Hall to find work with the Teamsters. I’m standing in the bullpen, as they call it, with all the other guys, and this friend of mine walks over to me. He says, “Hey, Al. What are you doing here, man?”

I say, “What? What are you talking about?”

He says, “I can’t put you to work. You’re worth $250,000. I gotta put these other guys to work.”I say, “What do you mean? I didn’t get no money yet. I haven’t heard anything.” But I go back home to the hotel. I get there and I’m looking at my three kids and my wife. We have a 21-inch TV, remote control. I wind up taking it out and getting in touch with some lifeguards I know, tell them I have a TV for sale. The chief winds up making me an offer. I sell him the TV – I guess it was about 100 bucks – so we can have some food.

By Christmas I still haven’t heard anything from the IGFA. Christmas Eve comes and I’m in the hotel with the kids. We’re eating peanut butter and crackers. Ain’t much going on.

The manager of the hotel comes by and says there’s a phone call for me in the front office. I go out to his office, ’cause we didn’t even have a phone in the room. They shut them all off. I pick up the phone and the guy comes on. He says, “Albert, I’m Elwood K. Harry. I’m the president of the International Game Fish Association. There’s no more fitting time for me to call you than Christmas Eve. We reached a decision. We unanimously voted to give you the new all-tackle world record, as well as the 20-pound-test record. There’s a limousine coming down from New York from the man who owns the tackle company. He’s bringing you to New York, to Rockefeller Center. You’re going to stay at the Hilton. He’s flying in on the Concorde from Paris. He’s bringing you your money and he’s going to pay you the $250,000. Congratulations to you. Job well done on catching that fish. If you ever get down here to Florida, come and see us and say hello. Now God bless you, Albert, and merry Christmas.”

Well, we make arrangements to have someone look after the kids because we don’t know how long we’re going to be in New York and what’s going to happen. I wind up having somebody buy me a jacket and a tie. We get in the limousine and the weighmaster guy is in there, along with his wife. We all head off for New York.

We arrive at Rockefeller Center and check into the Hilton. In the room are bottles of champagne and a basket with every type of fruit in it. My wife and I look outside and there’s the building where the ball comes down on New Year’s, that wedge-shaped building. And we’re looking at each other, and we’re saying to each other, “Can this be real? Is this a movie? What is this?”

The next day we take a limo to the Explorer’s Club in Manhattan for the ceremony. That’s where they made the movie The Verdict with Paul Newman. Members include Admiral Byrd, the astronauts. They have moon rocks there. They have stuffed polar bears, elephants, Cape buffalo, lions. It’s a real men’s club. When I get there they take me to a room and give me cognac and a cigar. After a while, a couple of gentlemen walk in and say, “Al, are you ready?”

I said, “Yeah, let’s go.”

We walk up to these big sliding doors, must be 12 feet high, and I see all these people sitting at tables with tablecloths and napkins and crystal and waiters. There’s a woman representing the governor from the state of New Jersey. I see my wife. She’s sitting with the Guinness Book of World Records people from Niagara Falls. There’s sportswriters all the way from Oregon, Maine, Florida. They bring me out and I stand next to the podium.

The owner of the tackle company walks up and says, “Albert, I really wish you were using one of my products. Couldn’t you tell them you were wearing a hat or a belt buckle with my logo on it or something?”

I say, “No, I can’t.”

“That’s all right,” he says. “Now, if you’ll turn around and look at this, you’re gonna like it. I turn around and this check comes down from the ceiling. It’s about 12 feet long, five feet high, has my name on it, and it has the $250,000 up there with all the zeros on it. And as I’m looking at it, it’s dawning on me that this is real. This is absolutely real.

When we get back from New York, I deposit the money and rent a car. We take the family to Disney World. But before we leave I go to see my friend who was with me that night on the jetty. I hadn’t seen him in a while. I don’t know why he wasn’t invited to New York, to the award ceremony, but it wasn’t my place to invite anybody. And I still don’t know what arrangement he had made with the guy who owned the tackle shop. I don’t know what they worked out. When I get to his place, I say, “Hey, what’s up, man?”

He says, “Well, if it isn’t the millionaire! What’s up champ?”

I say, “Hey, I brought something for you. I wanted to do something for you and your family.” And I give him a check for $10,000. That’s the last time we ever spoke.

So we go down to Florida to get out of the snow and ice. When we get there it’s 70 degrees. It’s fabulous. Palm trees, beaches. The kids are having a ball. We see Mickey Mouse, the Disney parades. We stay right next to Disney at one of the hotels there. I just want to mend my wounds. I’m feeling pretty beat up. And we are scared, nervous. Nothing like this has every happened to us. My wife’s parents are both dead. She doesn’t have anybody to hold her in Jersey. I really don’t have anybody to hold me around either. My grandmother is dead. My grandfather is gone. It’s just us and the kids.

When we get back to Jersey, I get a note saying that the Sportsman’s Federation of New Jersey was making me Sportsman of the Year. I also get invited to the New Jersey Game & Fisheries’ annual event. They want to give me a plaque for catching the New Jersey state record striped bass. I wind up going up there, driving up with my sister and my brother-in-law and my wife.

When we get there, I’m sitting at this table and this guy’s talking to me. He identifies himself as a publisher from New York. He says, “You know, man, you robbed your kids and you robbed yourself and your wife.”

I say, “What are you talking about? Who are you?”

He says, “You gave everything away for free, and they didn’t have to pay you. You didn’t get a dime. You’re a fool. You’re stupid.”

Just as I’m getting ready to stand up, my brother-in-law grabs me by my arms.

When I get up to the podium, this guy has a plaque for me. He says, “Albert, we want to present this plaque to you for the New Jersey state record.” But they have the date wrong and they have my name spelled wrong. He says, “Well, this is close enough, man. Here, take it.”

By spring I feel that New Jersey is closing in on me. I don’t want to be there no more. It’s time to leave. I tell my wife that I’d like to move up to New England, where I used to fish commercially. We wind up looking for property up there. I find a beautiful saltbox home, three bedrooms, three baths, a two-car garage, five acres of land. I buy it for my family.

We also decide to travel some more, to take the prize money and enjoy it. We travel extensively. We do what we want to do with our family. Sometimes we see people on hard luck and having tough times and we give money anonymously. We can’t let people know that we help people and give money to charities. We don’t want our names mentioned, because everyone will have their hand out. They think we’re rolling in money.

People don’t realize that if it wasn’t for the $250,000 prize, I would have gotten next to nothing for catching that fish. But everybody throws that in my face – with $250,000, what am I crying about? It’s the principle. I mean, come on, man. Ted Turner didn’t stop at one million, Donald Trump didn’t stop at a certain amount of money. You’re supposed to make money and share the wealth.

One of the things I can’t understand is when you have these news reporters come up to you and tell you they want to do an exclusive story, or they’re freelance writing and want a story. As soon as you ask them what they’re going to pay, they tell you that they have to talk to their editor about it. And then they come back and tell you that the editor says they can’t pay you anything. Here these people are, traveling, getting their expenses paid, hotel, meals, a salary. Their newspapers are selling millions of copies and they start crying poor. They don’t want to give you a dime. I hated that. I had people try to coerce stories out of me. Guys come down from New York telling me they’re writing a book and they want an interview. Then, when I go to look for the book, the book never even came out.

You know, and I ain’t joking when I say it, if I ever hooked another world-record fish I would think of cutting the line and letting it go. My oldest son says to me, “Dad, you should never pick up a rod ever again. It ain’t worth it.” I hope this story is going to open the eyes of anyone who thinks that catching a world record will make everything fabulous and wonderful. Let’s talk about reality here.

I had people following me, watching me. I had all sorts of crazy things happening – phone calls, cars pulling up on our property with the lights off. People would pull up while I was fishing. I’d go to walk over to the car and they’d take off. When I went back fishing, they would pull up again. I’d try to walk up to them again and they would take off. I don’t know what these people wanted. I have no idea. I wish I could have gotten a good attorney to advise me.

One time I went up to Maine on a trip and I walk into this bar there. It’s like a little hunting bar. And I’m sitting there, and I had a jacket on with these patches for the tackle companies. Being a fool, I’m wearing these patches and these guys ain’t paying me for them, but I’m advertising for them. They don’t give a damn about me. This guy sees the patches on my jacket and he says, “What’s all that stuff about?”

I says, “I’m the world-record holder for striped bass.”

He says, “That’s a damn lie. If you say that again I’ll come around the bar and break your jaw. I’ll fracture your skull. The world record was caught in Maine. You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.” And the bartender’s standing there. Well, I got my stuff and I got the hell out of there.

It shook me up. I mean, here I am, the world-record holder for striped bass, and somebody wants to do me bodily harm because of it. I started thinking about what I did wrong. I didn’t understand it. I’m just a regular guy. I learned. I would never wear any patches on any jackets, hats or shirts, or anything advertising these companies. Never again. Not for free I wouldn’t do it.

I’ve had guys ask me, “You’re the world-record holder for striped bass? Why are you so quiet, man? Why didn’t you tell us who you are?” Because of things like this:

One time I’m in Brigantine, New Jersey, and there’s a fishing tournament going on. I thought I’d go over and see what they are catching. There’s a whole bunch of guys there, and they’re having a little fish fry and beer bust. I walk up and this one guy’s glaring at me. I never met this guy before in my life. He comes over to me and says, “You’re the world-record holder for stripers?”

I say, “Yes.”

He says, “How many stripes does a northern striper have and how many does a southern striper have?”

I say, “I really don’t know. I didn’t know there was a difference.”

He says, “Yeah there is, you stupid ass. I told people that you don’t know what you’re talking about. You don’t even know how many stripes there are on a striper!”

After I moved out of Atlantic City, I tried to go back just to visit. I pull up to the boardwalk and get out of the car with my two sons and we start to walk up the ramp. I get up to the top of the ramp and there’s my cousin. He comes down the boardwalk, starts shoving me, poking his finger in my chest, telling me I deserted him. He said I was going to build him a tackle shop, said I was going to give him $10,000 like I gave the other guy. He’s telling me my grandmother and grandfather would roll over in their graves if they knew what I turned into. I ought to be ashamed to show my face in Atlantic City. And he’s doing this in front of my sons. We start backing down the boardwalk. He shoves me real hard and I go back against this rock. I laid the whole back of my foot open about five inches. We get back in the car. We drive out of there. I should have had him arrested for assault. This is what your family can do to you over money.

My sister calls me up and tell me she needs money. She’s cheating on her husband with her minister and says that she found religion. The woman’s out of her mind. When I won’t give her the money, she tells me I should shove the money, and she wishes that I would die.

I’ve got an older brother who lives in Hawaii. He’s a retired E9 Chief from the Navy. He married a Japanese girl from Okinawa and has a couple of kids. He finds out I have money and he contacts me. Tells me he’s losing his home. And here he is with a chief’s pension. God knows how much a chief gets after 30 years in the military. I break down and send him $10,000. He tells me he owns land in Bakersfield, California, and that he’ll give us that as collateral, or he can give me a sword owned by his wife. It’s a Samurai sword, worth thousands of dollars. But I don’t take anything from the guy. I just want to help him out.

Later, I come to find out he’s a used-car salesman, working part-time, and he’s an alcoholic. When I ask about my money, he tells his kids and his wife that I’m nuts. He changes his phone number, his address, never pays me a dime. Think about lending money to your family!

It gets worse. I get a call from a former lifeguard who lives in Cleveland. He’s in the money-management business. He deals with people like Mario Andretti, Arnold Palmer, Dick Butkus, Barbara Streisand, Johnny Mathis. This guy wants to take me on as a client. Well, he had me invest some money in stocks and bonds, stuff I know nothing about. I wound up getting wiped out. I lost money.

Now it doesn’t give me any pride to tell people what eventually happened. This is the seriousness of catching the world record, winning the richest prize, and all these other things. We actually wound up losing our home. We lost all our money. We have no life insurance. We have no medical insurance. We wound up living in a car and living in motels with our children. And I was too embarrassed to ask anybody for help or tell anybody what our situation was. But I think it should be told. This is real life. This is the truth I’m telling you. Was it all worth it? Yes. They say life is a roller coaster. You have highs and lows. If you don’t get on the roller coaster you never enjoyed life. Jackie Gleason said that fortunes are to be won, fortunes are to be lost and then won again. He says life is terrific. And he’s right. Life is fantastic.

If you get to Florida and visit the IGFA headquarters, the new Fishing Hall of Fame, the replica of my world-record fish is hanging there when you come in the door. It’s right above the world-record largemouth bass. There’s also a painting of me standing on the rock jetty, and it shows the world-record fish coming up and taking the lure. The artist is a famous painter. He donated the painting to the IGFA. It’s a $20,000 painting. It’s called “The Moment of Truth.”

Editor’s Note: If you missed Part I, you can read it by clicking here.