It was late afternoon, and we were running southwest along the ocean-side flats of the Lower Florida Keys. We’d spent the past few hours poling a productive spot where we’d hooked a couple nice tarpon, and now, crusty with salt, we were headed back to the Bahia Honda Sporting Club, where a good meal and hot shower awaited.

It had been an exciting several days at this special place, full of camaraderie, laughs and many fish, and as the heavy June air whipped cool with the breeze, we suddenly noticed a disturbance out front. Capt. Gordon Baggett yanked back on the throttle, and as the skiff came down off plane, dozens of long, black shapes began darting out from below the hull.

This day wasn’t over just yet – we had run smack-dab into a big pod of fish!

Luckily, the tarpon were only temporarily bothered – they were moving quickly but soon began rolling happily again on the surface as we eased to the outside edge.

Baggett jumped onto the poling platform and began pushing hard to keep alongside the school while I snuck onto the bow and fired a few casts to the approaching fish. No takes. Another cast. Nothing. Finally, the line suddenly came tight, and a big fish rocketed out of the water like a lassoed bull.

My throat tightened as the fly line jumped off the deck. But just then, it fell slack, and I knew the fish was gone. I stood there for a moment, frozen, and then chuckled. Gordon’s strange little stiff worm had fooled yet another one.

The Evolving Keys Tarpon

There’s no question that tarpon fishing in the Keys – and throughout the state of Florida, for that matter – has become more difficult over the years. Certainly, the wily old silver king remains the top attraction for fly-fishers, and for good reason. Yet while duping them into eating a fly has grown tougher, it’s had a silver lining, as well: It’s forced the best guides in the business to become even better, developing new, innovative techniques to consistently fool these fish with the long rod. It’s a concept I was reminded of repeatedly during my trip to Baggett’s lodge.

No one knows better the changing nature of tarpon fishing than Dr. Gordon Hill. A retired orthopedic surgeon, Hill moved to the Lower Keys in 1962 and witnessed firsthand the “golden era” of tarpon fishing while becoming one of the legends of the sport.

“In the old days, the tarpon would come in great droves, to the point where you could practically walk on their backs,” he remembers. “It didn’t take a whole lot of expertise to hook one on a fly rod, and you didn’t have to get too fancy with your flies or your retrieval.”

My, how things have changed.

Tarpon today are pounded like never before. With the emergence of so many new fisheries along their annual migration routes, they never get a break – and they’ve seen it all. Still, hordes of fish cycle through the Keys each summer, and while they’re smarter, they’ll still readily eat a fly for those who do the right things – and perhaps more importantly, for those who dare to try something different.

For nearly a dozen years, Baggett, like most good guides in this area, closely guarded his best tarpon techniques like intellectual property. But he revealed a few of his tricks during our visit. For the most part, they revolve around a fascinating little fly he calls his Stiff Worm.

A Simple Little Stick

Worm fishing, of course, is nothing new. Men have been imitating palolo worms with fly patterns since before Baggett was born, and veteran captains like Jake Jordan and Bruce Chard have been fishing them successfully in the Lower Keys for decades.

But Baggett took a different approach when he first arrived in this area over 10 years ago, and it made all the difference for him.

It didn’t come easily, however.

Baggett spent a couple humbling seasons trying to learn the fish around the famed Bahia Honda channel. He fished alone in these days and became increasingly frustrated – until he witnessed his first palolo worm hatch. Baggett managed to collect several worms, studied them closely and then went to work on a pattern.

His creation was original and unique – and, surprisingly, it generated a system that he now fishes all the time, and not just on the ocean side or during worm hatches.

I first saw Baggett’s worm fly on the second day of our trip, and admittedly, I wasn’t overly impressed. It appeared not much more than a stick on a hook – kind of like a trimmed-down coffee stirrer! Our first day had been spent on a different boat, and we’d thrown primarily rabbit-strip patterns along the ocean-side flats. We did OK, but over thenext couple days, the stiff worm produced decidedly more eats. And it became apparent that – like many other excellent tarpon patterns – the fly worked precisely because it was different.

Baggett’s epoxy fly is all about shape and profile: a simple-looking stick, designed stiff on purpose to remain straight in the water while retaining the subtleties of a real worm. Like most good tarpon flies today, it is tiny – just a couple inches in length. What’s more, the worm’s head region is extremely creative, formed by snelling the shock tippet onto the upper shank of the hook, generating a very realistic yet simplistic appearance.

Of course, a simple-looking design can sometimes belie a real winner.

“I’ve looked at that fly underneath, the way a tarpon would, and it sure looks like the real thing,” says Hill. “It’s one thing for a fly to look like the forage or the hatch in the tackle box, but it’s another thing to look like the real thing underwater.”

All about Speed

Hill is quick to point out, however, that the key to this pattern, like the key to any good tarpon fly, is in its presentation and retrieval.

During our trip to the Bahia Honda Club, Baggett emphasized that sticking to a few simple concepts greatly helps produce results.

“Speed of the retrieve is critical,” he says. “Consistent speed is critical, and the fly swimming straight is critical, too. The tricky part – the reason there’s not one fixed retrieval speed – is that the water and current are always doing something different. So the speed of the fly in the water should be the same as that of real worms, and our hands move slower or faster based on what the water’s doing.”

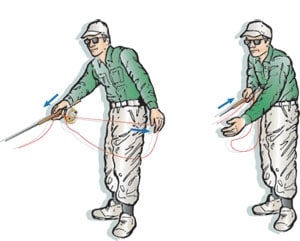

Baggett has his clients strip the fly with a methodical push-and-pull kind of action. With the rod jutted away from the body and toward the cast fly, a strip is made with the left hand (Illustration A); then the line is pinched with the rod hand, and the entire fly line is pulled toward the angler (Illustration B). When the rod comes tight to the body, the angler then pushes the rod back toward the fly while simultaneously stripping again with the left hand. The process then repeats itself, creating a steady, non-stop swimming action like that of a palolo worm.

It’s easy to find the rhythm once you get the hang of it, but as I learned, it takes a bit of practice to prepare for a strike, as one could occur anytime during the transition of moving the rod forward or backward.

When fishing this fly along ocean-side flats – as is the case with other worm patterns – Baggett says it’s best to be positioned on the outside of moving fish and to work the worm toward the Atlantic, as this is the same natural direction that palolo worms swim. It certainly helps to retrieve this way during non-hatch situations – which is almost always – but it is absolutely critical during an actual hatch when the water is alive with worms.

But more importantly, Baggett says, is adhering to the traditional, time-honored method of trying to generate a head-on shot and keeping the fly positioned directly in front of an oncoming fish, which conceals the fly’s hook and keeps it in the eating zone longer.

From Ocean to Backcountry

Of course, it’s natural for tarpon to eat worms along the ocean-side flats and in areas where the critters emerge from the coral to spawn. During our June trip, we focused exclusively on this side and managed to hook several fish each day despite never seeing an actual hatch.

But Baggett learned long ago that his little fly worked equally well on tarpon in the backcountry. When sight-fishing in visible conditions out back, it can produce very well in the hands of an experienced caster who can place the fly close to a tarpon’s nose. Because of its discreteness and slim profile, however, it doesn’t push water and won’t work well when blind-cast.

It performs best – regardless of whether fishing out back or along the ocean – when conditions are demanding, such as under bright skies, in clear water or over a light-colored bottom.

Hill says at first he was a “disbeliever” of Baggett’s claim that the pattern worked well on fish far from the ocean flats. But after experimenting with the fly, his opinion changed.

“I couldn’t see how in the dickens matching the hatch when there wasn’t a hatch could work,” he remembers. “Especially when the tarpon were feeding on other things and when there were no worms around. But there is something in that tarpon’s brain that makes him strike the fly anyway. After having fished with Gordon many times, I’m now a believer. Gordon is right.”

Many great tarpon patterns and fishing techniques have been developed throughout the years in the Florida Keys. From the Stu Apte Tarpon Series to the Orange Quindillan to the Toad, they continue to emerge and evolve along with the fish. Eventually, though, even today’s best tarpon flies will be replaced by the great new patterns of tomorrow.

In 15 years, who knows what the top tarpon patterns will look like? The most amazing thing, however, is just how much work and thought goes into the creation, development and evolution of a simple little bug. Or, in this case, a simple little worm.

RODS: 12-weight is ideal, though it’s possible to use a lighter rod in calm conditions and for smaller fish. Attach to a high-capacity reel with a smooth drag, such as an Abel Super 12, Mako 9600 or Tibor Gulfstream.

LINES: Intermediate sink-tips, such as a Cortland Ghost Tip, are most common, but floating lines, such as clear Monic lines, can also be very effective in certain conditions and especially in the backcountry.

LEADERS: Length depends on clarity, but a tapered 9- to 15-footer will typically get the job done with 12-, 16- or 20-pound class tippets and 60-pound bite tippets.

FLIES: Small patterns have been the name of the game for some time now. Try a Gordon’s Stiff Worm on a 1/0 hook during your next trip, and don’t forget some small Toad flies and Bunny patterns.

OTHER: Line-management issues can arise when it’s howling on open ocean-side flats, so consider a stripping basket. Of course, don’t forget quality, polarized glasses with a brown/amber tint and a broad-billed hat to help you spot fish.

The Lower Keys boast many fantastic independent guides, but if you’re looking for an all-inclusive-style experience, Bahia Honda Sporting Club is tough to beat. In fact, it’s the only lodge of its kind in this area, offering first-rate accommodations and a team of excellent guides.

The lodge is more or less a mansion on a 16-acre waterfront property sitting in the heart of some of the finest tarpon waters around. It can accommodate groups of 6 to 8 guests, and it employs five top-notch guides, a hostess and a superb chef.

The daily routine includes a leisurely breakfast cooked to order, followed by a stroll down the dock to your skiff and a morning fishing session; then a run back to the lodge for lunch, followed with more afternoon fishing – oftentimes until the sun goes down. The day concludes with a gourmet dinner featuring fresh Florida game and fish entrees taken locally by the lodge’s guides.

It’s truly a first-rate operation. From the food (which is as good as any high-end restaurant) to the convenience to the camaraderie and fishing, the lodge is absolutely unique to this area. It makes for a wonderful Lower Keys experience.

For more information, visit www.bahiahondasportingclub.com, or call 305-395-0009.