|| |—| || |DEAD IN THE WATER: What happens when a trawler is headed straight for your boat, and the motor won’t start? Illustration by John Hendrix| Temperatures had only climbed into the 50s by mid-afternoon on July 1, and the wind carried mist across the parking lot of the state boat launch in Hampton Harbor, New Hampshire. Despite the conditions, my friend Paul Johnson and I tossed our striper gear into his 16-foot tin boat and headed out. We figured a little stormy weather wouldn’t kill us.

Right off the launch, I started catching schoolies, and the sky was beginning to clear-both good signs, I thought. We motored out to the Hampton River Bridge. Stretching from Seabrook Beach to Hampton Beach, the bridge spans the quarter-mile-wide mouth of Hampton Harbor, which opens into the Atlantic. There, we made the first of several drifts on an incoming tide. With a smallmouth rig and eight-pound test, I was tossing a big yellow bucktail with a porkrind trailer and jigging it back across the current-and I was nailing fish.

What I couldn’t seem to do, however, was land any of them-and I was in no small hurry to do so before my buddy did. After losing a monster that raked the line across the underside of the boat and broke off, I switched to a big salt water rig with 20-pound test and was just cinching down the knot on my jig when Paul pointed over my right shoulder.

“Look at that,” he said, peering past me. “This guy is going to come really close to us.”

About 100 yards off, a 45-foot fishing trawler was moving toward us. I shrugged it off and kept fishing.

“I’m telling you,” he insisted. “He’s coming right for us.”

| |BETTER DAYS: Mike Lovell is a passionate New England striper fisherman. Photo: Courtesy of Mike Lovell| I looked up again and was a little stunned at what I thought was a captain’s arrogance to pass by a stationary fishing vessel on a course that would bring him within 30 feet of our boat. But I still didn’t exactly stop fishing. It sounds crazy now, but it seemed so impossible that this huge fishing boat would actually ram us that I was positive it wouldn’t. I was sure the captain saw us.

Finally, with the trawler only 40 yards away and Paul yelling, “He’s coming right down on us!” I let go of the handle on my fishing reel. The big boat was coming full throttle, but given its course, I could see it wasn’t actually going to hit us.

It was, however, going to throw a huge wake our way. So I set my feet for what I imagined would be a wild but probably harmless ride-a little like surfing.

Meanwhile, Paul was wisely scrambling to get us out of there. He punched the throttle of our idling outboard, but to his horror it only squealed for quarter of a second and died.

He grabbed the starter rope and began pulling when the trawler notched over a little to its port side-that is, a little more toward us. Paul dropped the rope, stood up and began waving his arms and yelling. I quickly joined in.

While both of us screamed hysterically, I was watching the hull of the trawler. Even given the new angle, I still wasn’t totally convinced it would connect with our boat. But then the whole scene changed. At just 20 yards, the trawler notched again to the port side, and the immense white bow turned to face us dead-on. It blocked out everything else. Suddenly, there was only this towering wall of steel and two hard facts: He doesn’t see us. He’s going to hit us.

T-Boned

I tried to jump out of our boat and had barely cleared the gunwale when the bow of the trawler smashed into my head and shoulders. Angling into and above me, it was like a wall coming down, forcing me underwater. I slid deeper and deeper down the side of the trawler’s hull into a kind of murky green darkness. Completely disoriented, all I could think about was being chopped up in the trawler’s props. I kept imagining this movie-like scene of giant, whirling steel blades and me in the middle of them. I turned to prop my feet against what I guessed was the bottom of the fishing boat and pushed off hard. Swimming away from the boat, I told myself I would stay as deep as I could for as long as I could, until the props had passed overhead.

I stayed under until I thought my lungs would collapse-until even the thought of swimming back toward the surface headfirst into the props couldn’t keep me down a second longer. When I popped up, the trawler was about 100 yards away. I expected to see my buddy and our boat nearby. But I didn’t. I looked left and right, and there was absolutely nothing around me.

| |EARNING HIS STRIPES: Paul Johnson is a veteran angler and boater. Photo: Courtesy of Mike Lovell| I didn’t know it at the time, but Paul was also about 100 yards away, and moving farther into the distance at the exact same speed as the trawler-because he was pinned to the bow of the big ship.

As I had jumped out of our boat, Paul was sitting in the stern on a brand-new swivel seat he happened to be very proud of. That’s when the trawler rammed the 16-footer, driving the port-side gunwale slightly underwater and bending it around the front of the ship’s bow. The starboard gunwale shot skyward, meanwhile, and there the boat remained stuck, held by water pressure as the trawler chugged forward at full speed. And right with it-pinned upside down with his feet in the air, his head barely above water, and his fingers gripping the new swivel seat-where he still sat-was Paul Johnson, screaming futilely to the ship’s captain.

For some reason, the trawler was now speeding toward the rocks of the Hampton Beach breakwater. Having already been plowed though the water for 100 yards, gasping for breath through froth and spray, Paul said he was becoming more and more convinced that he would also be ground up against the rocks of the sea wall. He told himself that his life was about to end.

But getting close to the breakwater is what saved him. The Hampton Beach area is something of a tourist destination, and the breakwater is a hot spot where folks kick back and gaze out onto the ocean. On the early summer day, there were dozens of people there, and upon seeing a man pinned to the bow of a fishing trawler, some of them started jumping up and down and waving their arms in an effort to gain the attention of the boat’s captain. Mercifully, the trawler throttled down. Our boat came unstuck as soon as it slowed and capsized. And Paul slid underwater.

The Aftermath

Everything in the 16-footer-tackle boxes, coolers, PFDs-must have been sucked into the props of the trawler. All of it was chewed up, smashed to pieces and scattered everywhere. Somehow, Paul was able to swim away from the trawler and toward shore. He wasn’t having an easy time of it, however, until suddenly his new swivel seat-the one he’d been raving about all day and had been sitting on all through the worst boat ride of his life-popped to the surface. He grabbed it and floated toward shore while several of the people there tore off their shirts and shoes and jumped into the water to help him reach the rocks safely.

When he got to the breakwater, Paul immediately began yelling my name, and the people there joined in, searching for me in the water in front of them. From about a half-mile away, I could hear them shouting; I could even make out my name drifting toward me over the water…but their voices were getting fainter.

The current sweeping out into the harbor’s bay was taking me with it, and farther from the breakwater. I’m not a good swimmer, but I could see a boat moored no more than a quarter-mile away and thought I could make it. I took a course perpendicular to the current and swam for what seemed like a solid 15 minutes. When I looked up from my sidestroke, the boat looked to be more than a half-mile away from me.

I tried again, but it was pointless. The current had taken me well into the giant bay. I looked around, and there was nothing. Not a thing I could swim for-not a single chance to save myself. I was tired. I figured I could tread water for another five minutes. But when I looked around again, there were no boats close enough to rescue me in that time. There was just a gray expanse of water in every direction. I had a sick, sinking feeling that this could be the end for me.

Then something appeared in the distance. There was no mistaking the trawler that had run over us, and it was moving closer on a zigzag course, obviously searching for something.

I waved my arms and saw the boat take a line toward me. I was relieved, but completely spent. I don’t have the slightest idea how long I’d been out there. What I do know is that I wouldn’t have lasted another 30 seconds if the trawler hadn’t pulled up beside me when it did.

I was amazed that the same boat that rammed us-so clumsily it seemed-could be steered so precisely within inches of me on one try. Some mates threw me a line with a loop in it, and I slipped it over my shoulder. Then I endured the awkward experience of being winched up and pulled onboard like the day’s catch.

Rescued

Once onboard, the captain looked at me and said, “Hey, I never saw you.” He obviously felt bad, and I wasn’t the least bit upset with him. I was thrilled to be out of the water, and to be honest, I wasn’t thinking straight.

I was unreasonably upset that I’d lost my new sunglasses in the ordeal, and for some reason, I assumed my buddy was fine. I figured he’d already started fishing again.

When I reached the boat dock, the police and marine patrol were waiting, and Paul had walked down from the breakwater.

“I thought I’d lost a best friend,” he said and hugged me-for the first time ever. It seemed completely bizarre to me.

Truth is, I don’t think either of us were in our right minds because when things settled down, we thought it was a big joke. We were laughing on the drive home when Paul sort of remembered that his legs really hurt. He pulled up his pant legs to reveal several big purple bruises and a horrible dent across his shins, all of which he apparently suffered during his ride from hell, but somehow he could not remember exactly how they got there.

We stopped in the emergency room, and even there, neither of us called our wives because we didn’t think it was a big deal. I just phoned my sister and brother-in-law to tell them our big, hilarious story. My sister called my wife and told her we’d been run over by a trawler but were fine. She was pretty concerned when I got home. I wondered why she had even bothered to wait up.

Finally, I went to bed. I closed my eyes and instantly began dreaming of sliding down the side of the trawler’s hull, down again into that murky green darkness. I could see the giant metal props whirling, and I then woke up in a sweat. It was two in the morning. I stared at the ceiling for hours, feeling very upset.

Eventually the phone rang.

“You sleeping?” Paul asked.

“No,” I answered.

“Me either.”

Dave Hurteau is a New York-based freelance writer. This is his second story for Salt Water Sportsman.

| Rules of the Road |

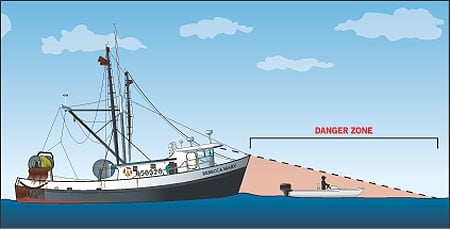

A TOUGH SPOT: A pilot’s blind spot can extend more than 100 feet. Illustration: Pete Sucheski When fishing in high-traffic areas, it pays to be ultra cautious. Here’s how.While inland and coastal waterways play host to hundreds of recreational boats, at the same time they also carry trawlers, barges, tugboats, towboats and even ships. Being aware of the constraints under which these vessels operate can arm recreational boaters with the best protection against danger. It could save your life. Refer to the United States Coast Guard website (www.uscg.mil) for comprehensive information on boat navigation rules. Meanwhile, here are five quick tips to keep in mind whenever you are fishing waters with high boat traffic or are in the presence of commercial vessels.A “blind spot” exists on large vessels that can stretch for hundreds of feet in front of them. Such vessels have a longer stopping distance, move with deceptive speed and make it difficult for you to maneuver and quickly get out of their path. Large vessels travel faster than you might expect, even in poor visibility or congested areas. It may take a fast vessel less than ten minutes to reach you once you spot it in clear weather, and in hazy weather it takes a lot less. At ten knots, a ship goes one nautical mile in six minutes; at 15 knots, it can be on you in four minutes. In addition, remember that in low visibility, ships navigate by radar, and small craft may not be detected. Large vessels must maintain speed to steer, and they must stay in the channel-the only place deep enough for them to operate. Many channels are unmarked. On some waterways, the channel extends bank to bank, so expect vessel traffic on any portion of the waterway.Always designate a lookout. Assign one person in a recreational boat to keep watch, particularly for fast-moving commercial traffic.Wear a life jacket at all times. More than 82 percent of those killed in boating accidents in recent years were not wearing life jackets. – Eds.|