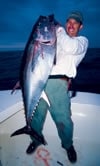

| Matt Hawkins battles a bluefin on spinning gear in the productive waters off Cape Ann, Massachusetts. |

It was the best of tuna, it was the worst of tuna. For eight amazing weeks last year, bluefin tuna ranging from 30 to 150 pounds tore up the inshore waters and wreaked havoc on tackle from the tip of Cape Cod to New Hampshire’s Isle of Shoals. It was a bluefin bounty the likes of which hadn’t been seen in years, and gave a new generation of anglers its first taste of what these powerful fish can do. For many, it made all other types of fishing seem woefully inadequate.

Not everyone went home happy. A major problem was landing the fish. Since casting small lures on relatively light spinning and baitcasting gear was the best – and sometimes only – way to hook up, tales of stripped reels, bent hooks, broken rods and various other forms of tackle torture soon became legion. The tuna showed no mercy, and by mid-August there wasn’t a tackle shop from Provincetown to Kennebunkport that had a Penn 9500 spinning reel or spool of 60-pound braided line in stock. But then again, many anglers didn’t mind losing some gear, because just hooking one of these incredible fish from their own boat was the thrill of a lifetime.

Bass and Bluefins

Last season saw the tuna feeding on huge “bait balls” of juvenile menhaden. Some surface blitzes lasted 30 minutes or more.|

The other wonderful thing about the 2002 tuna was how accessible they were. On many days the schools were less than three miles from shore, within easy reach of anglers in small boats. And in some cases no boat was needed at all. It’s estimated that ten or so bluefins have been taken by shore fishermen in the last few years, prompting the National Marine Fisheries Service to consider adding a shore permit for tuna!

Tuna appeared throughout Massachusetts Bay in ’02, but one of the most dependable inshore spots was Cape Ann, Massachusetts, an area fished by charter captains Nat Moody and Derek Spengler of First Light Anglers. The fish often gathered in 100 to 180 feet of water, and were so close that the two skippers and their clients were surrounded by busting bluefins just ten minutes after leaving the dock. “It was great,” says Moody. “The feed didn’t get going until around 7:00 a.m., so you could fish for striped bass in the early morning and head out for tuna afterward.”

Another charter captain who experienced the incredible fishing off Cape Ann was John Pirie of On-Line Fishing Charters. Pirie first encountered the tuna in early August while looking for bluefish. “I had a client and his son with me who wanted to catch some bluefish. I had been hearing reports of big schools of blues busting on the surface off the northeast corner of Stellwagen Bank, so we went out to take a look. Turns out that the fish were actually tuna. We were covered up with them for hours!”

| ### Tuna Tools |

Metal jigs and spoons rigged with single hooks proved highly effective on last year’s tuna, which were mostly keyed on small baitfish.|

When it comes to casting jigs, soft-plastics and other lures to busting bluefins, spinning gear is a lot easier for most anglers to work with. Derek Spengler and Nat Moody use Shimano Thunnus 16000 and Penn 9500 SS reels. They spool up with 50-pound Cortland Black Spot braided line, tie a Bimini twist in the end, then attach an 80-pound swivel with an offshore swivel knot. To this they tie on four feet of 30- to 50-pound fluorocarbon, depending on the size of the tuna. The rod is a seven-foot, heavy-action stick rated for 20- to 40-pound line. In the fly-fishing department, their outfit of choice consists of a 14-weight Winston rod and a No. 5 Abel reel filled with 900 yards of 50-pound Cortland Black Spot as backing and topped with an intermediate line and a straight 44-pound-test fluorocarbon leader. Their most productive flies last season were four-inch baby bunker patterns tied on 6/0 Trey Combs salt water fly hooks.

John Pirie also uses Penn 9500 spinning reels, but prefers 40-pound Yo-Zuri Hybrid line, which holds up well to long battles with stubborn tuna. His leader is two feet of 60-pound fluorocarbon attached to the main line with a surgeon’s knot. At the end of the leader is a 90-pound SPRO swivel. As mentioned, Pirie also upgrades his lures with heavy-duty split rings and 5/0 to 7/0 Siwash stainless hooks. The hooks are open-eye models, which makes rigging a snap. – T.R.

Pirie saw that the fish were feeding on small “spike” mackerel, so he had his clients cast metal jigs into the breaking schools. “We hooked up seven or eight times that day, but didn’t land one,” laments Pirie, who only had 15-pound bluefish gear on board. After that experience he was better prepared.

To the south, Captain Steve Moore found the tuna off Provincetown from August to October – as long as sea conditions allowed him to get out in his 18-foot Parker. Moore would launch in Barnstable Harbor and head north toward P-town, looking for birds and tuna on the way. He often found them as close as one mile from the beach.

“One time I chased a school that was feeding on bluefish within surf-casting range,” he recalls. “Guys on the beach could actually reach the fish with their plugs! Those bluefish were probably scared out of their minds. They wouldn’t leave the surf zone.”

Massive Bait Balls

While the tuna’s catholic diet allowed them to prey on whatever forage was available, their primary feed during the 2003 season was small menhaden. Moody and Spengler confirm that the bluefins were feeding on spike mackerel when they first arrived in August, but soon switched to the juvenile menhaden, also known as baby bunker.

“Bunker were the key (to the fishery),” says Moody, pointing out that the inshore waters north of Cape Cod were loaded with schools of the three- to four-inch “minihaden.” The tuna would herd the baitfish into tight masses on the surface, then tear through the middle of the bait ball or mow through it in a single line. Sometimes the bait was so thick that the fish would stay up for 30 minutes or more, leisurely taking turns swimming through the ball.

“The trick is not to break up the bait ball,” Moody explains when asked to describe his fishing strategy. “Stop a good 60 yards upwind of the school and keep the motor running. The fish will typically move upwind as you drift down on them. Once you’re past them, circle around for another drift. By the way, I don’t think the boat spooks the tuna – it spooks the bait. They see this big shadow looming above them and take off.”

Pirie also advises a calm, measured approach. “Don’t run over the bait or get too close to the school. If you do, the bait may even hide under the boat. The tuna will follow the bait, but you won’t be able to cast to them. That happened to us last year. We could actually hear the tuna banging against the hull!”

Casting Call

Capt. John Pirie, right, and Mike Hilton, display a 75-pound fish that fell for a metal jig last summer. |

Because last year’s tuna were so dialed-in to the small menhaden, they typically ignored trolled lures and spreader bars, although these did work on occasion. Chunking was a definite waste of time. Even live-chumming didn’t work, because there was so much bait in the water. Casting lures worked best, and the top offerings were metal jigs, soft-plastic shad-bodied baits and flies that closely matched the natural forage. These would be cast into the breaking schools and retrieved slowly. At times, letting the lure sink below the bait was the secret to hooking up – and the ticket to hooking the biggest fish, which often cruised below the smaller tuna. Pirie connected with a few 300-pounders this way, which wasn’t always a good thing.

Hot lures in last year’s fishery included the Yo-Zuri L-Jack, Hydro Metal and Dual jigs; the Crippled Herring; the Hopkins No-EQL; the Acme Kastmaster, and the Mega Bait soft-bodied shad. Moody adds that poppers also worked at times, and that flies could sometimes out-produce metal lures ten to one. The drawback to using fly gear on 80-pound tuna, however, is that the fight often lasts three hours or more.

Capt. Steve Moore holds a 60-pound tuna taken on fly gear by Peter McCarthy off Provincetown, Massachusetts. Note the broken rod.|

Off Provincetown, Steve Moore had great success with Storm Wild Eyes soft-plastic baits rigged on one-ounce jigheads. “Anything that had a dark back and light belly worked well,” he says. “If you could get the bait in front of them, it seemed you’d get a hit every time.” Moore adds that topwaters such as the Storm Rattlin’ Chug Bug also worked well on occasion, and that flies could be awesome as long as you could get close enough to present them to the tuna.

Tackle Terrors

As many anglers learned the hard way, lure hardware had to be upgraded to handle the tuna, which routinely bent hooks, opened split rings and broke swivels. After a few unpleasant experiences, Pirie began re-rigging his metal spoons and jigs with 5/0 to 7/0 Mustad Siwash open-eye single hooks and No. 7 or 8 stainless-steel split rings. “The big rings look a little funny, but they work,” he says.

One problem of fishing soft-plastics was finding jig hooks that were strong enough to hold the tuna. Some creative anglers solved the problem by threading a strong, short-shank live-bait or circle hook through the lips of the plastic bait, then adding an egg sinker to the leader for casting weight.

A happy Dave Morel strains to lift a 125-pound bluefin after their two-hour slugfest off Gloucester, Massachusetts, last September. |

Then there was the question of rods, reels and line capacity. Although baitcasting reels hold more line, most anglers find it easier to cast with spinning tackle. Large spinning reels such as the Penn 9500, Shimano Thunnus 16000 or Daiwa Emblem 5500A saw duty on many boats last season, and were often filled with super-thin Spectra braid to boost line capacity.

After trying different brands of line, Moody and Spengler eventually settled on 50-pound Cortland Black Spot Spectra braid, which they found to be very tough and tangle-resistant. Pirie chose 40-pound Yo-Zuri Hybrid line, a blend of monofilament and fluorocarbon. This line isn’t as thin as braid, but Pirie found it easier to work with. However, he made sure to re-spool his reels with fresh line after each fish, and even went so far as to purchase a portable line-winding machine so he could fill his reels on the water (see sidebar).

Even with 200-plus yards of line, getting spooled was a real possibility with any fish over 60 pounds, which made for some exciting moments following the hook-up. “It’s all about reaction time,” Pirie says. “You typically have about 18 seconds to start chasing the fish or you’re in trouble. Double hook-ups get real interesting!”

| ### Fresh Line – Any Time! |

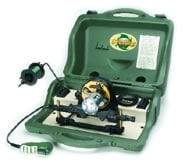

The portable Cyclone Winder makes it possible to strip and fill reels quickly, either at home or on the water. |

Bluefins can do a number on fishing line, especially when the fight lasts an hour or more. If you don’t replace your line often, you’re asking for trouble. During last year’s tuna run, Captain John Pirie took no chances and replaced his line after each fish. To make spooling up easier, even at sea, he purchased a portable line-winding station from Triangle Manufacturing. Called the Cyclone Winder, this handy machine comes in a rugged plastic case that’s about the size of a typewriter (remember those things?), and plugs into a 12V socket (also comes with an adapter for home use). It accepts both spinning and conventional reels, as well as fly reels, and holds filler and bulk spools (up to one pound) of line. The unit also has a line-stripping feature that allows you to strip reels in seconds. Perhaps the best part of owning such a machine, however, is that you can spool your spinning reels with absolutely no line twist – just like the professionals. The Cyclone Winder has a suggested retail price of $239.95 (plus shipping) and can be ordered directly from Triangle Mfg., Upper Saddle River, NJ; (888) 656-6686; www.cyclonewinder.com. -T.R.

Fast, maneuverable center consoles played a big role in achieving success in ’02. Not only did they make it easier to chase the fish, they were essential for working around lobster pots, which posed a major hazard in some areas. Being able to move freely around the boat also prevented a lot of cut-offs during the final stages of the battle.

Although last season’s tuna action was extremely dependable, the fish weren’t always easy to find. Moody and Spengler had a good bead on the bluefins’ whereabouts because they were out there every day (they hooked at least one fish a day for 35 consecutive days), but sometimes had to run as far north as New Hampshire’s Isles of Shoals and as far south as Boston to reach them. However, Moody says that the majority of the action north of Boston took place within ten miles of shore in an area stretching from Manchester, Massachusetts, to the mouth of the Merrimack River, including Ipswich Bay.

Pirie adopted a methodical search pattern on days when the fish failed to show in their usual haunts. Using his chart plotter, he would divide the ocean into four-square-mile blocks and work each one, stopping every two miles to scan for signs of bird activity on his 4 kW open-array radar and with binoculars.

Speaking of birds, Pirie notes that they can offer important clues in the hunt for tuna. “When you see gulls in the area, you know that the tuna and bait have been staying up long enough to make it worthwhile to stick around,” he points out. Terns, on the other hand, often point the way to fish traveling below the surface. “The terns can see the fish,” he says. “The lead tern is always right over the fish. By casting 20 feet ahead of the lead tern and letting the lure sink for ten seconds or so, you can pick off fish that you would otherwise miss.”

Of course, the big question on everyone’s mind is whether the bluefins will be back this summer. Both Moody and Pirie believe they will, based on the sheer amount of bait they saw last year. “I’m convinced that the major bait species go through inverse abundance cycles, each lasting about five years,” says Pirie. “In other words, when sand launce are up, herring-type baitfish (e.g., menhaden) are down, and vice versa. Right now we’re in the middle of the herring up-cycle, so we should see two more good years of bunker in the local waters.”

| ### Don’t Forget Your Permit! | ||

| If you plan to fish for bluefin tuna (or any type of pelagic fish) this year, you’ll need to possess a NMFS Highly Migratory Species permit. Cost is $22 and permits can be purchased by calling (888) 872-8862, or visiting www.nmfspermits.com. |

Whether or not this theory proves true, one thing is certain: there’s sure to be a lot more fishermen gunning for bluefins this season, which means that courtesy and cooperation will become important factors if the fish show up. In the meantime, get your boat ready, stock up on line and lures, purchase your tuna permit (see sidebar), and make sure you’ve got some back-up rods and reels. You’re going to need them if the tuna come to town.