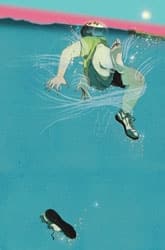

|| |—| || |Illustration: Marcos Chin| For the crew of the hangin’ loose the early july trip started off like any other offshore run for tuna. The four friends tossed the last dock line at nine o’clock on a Friday night, and slowly steered the 32-foot sportfisherman across Delaware’s shallow Indian River Bay toward its temperamental inlet.

Once safely through the breaking waves and swirling waters that make Indian River Inlet infamous, the vessel was greeted by a choppy and confused sea. The destination, a Mid-Atlantic tuna hot spot known as the Hot Dog, waited for them some 50 miles away. With the rough seas and the darkness of a late summer night the trip would take a few long and bumpy hours. Unfortunately, the crew would never make it to the coordinates Ryan, the owner of the boat, had entered into the GPS.

An admitted safety nut, Ryan decided to do one last inspection of the bilge pump before he could relax and enjoy the trip. With two of the crew members stealing a quick nap in the cabin and the remaining friend at the helm, Ryan leaned over the portside gunwale to take a look at the pump’s outlet. As he did, the boat slammed into a big wave. With a frothy whitecap rushing down its face, the wave violently jarred the vessel and forced Ryan off balance.

The props cavitated, the motors screamed, and the boat plunged down the backside of the wave. The impact of the hull crashing into the deep trough tossed the seasoned angler from the cockpit and into the lonely waters of the Atlantic Ocean. As the boat steamed past, just inches from his head, the roar from the twin 350-horsepower engines was deafening.

“I never even yelled,” Ryan says. “There was no chance they would hear me. It is loud back there.”

The boat’s white stern light flickered on and off each time the Hangin’ Loose disappeared behind the jagged swells. Soon, the only noise Ryan could hear was the tiny bubbles popping and fizzing all around him where the boat had ripped through the jet-black water just seconds ago. Ryan was slapped with reality. He was alone in the open ocean, six miles from the nearest beach, without a life jacket.

“I knew I was in trouble,” Ryan says. “When I saw the boat wasn’t turning around, I thought I was done for.”

The boat traveled for over an hour before the remaining crew realized something was horribly wrong.

Once reality set in and the crew faced the fact their friend was no longer onboard, an emergency call was relayed to the Coast Guard.

“It took them a while to know he was missing,” says Jeff Fox, the civilian controller who helped plan the Coast Guard search efforts.

“The two men in the cabin thought he was topside, and the friend at the helm thought he went below.”

The operations center at Coast Guard Group Eastern Shore in Chincoteague, Virginia, immediately obtained the vessel’s position and dispatched search-and-rescue crews to the scene. Within minutes, Coast Guard rescue vessels from Indian River Inlet and Ocean City, Maryland, were cutting their way through the heavy seas en route to the coordinates the frantic crew of the Hangin’ Loose gave them. The 87-foot patrol boat, Ibis, two C-130 aircraft and numerous helicopters would also assist with the search effort.

Meanwhile, back on land, Fox and a team of search-and-rescue officials using sophisticated computer programs tried to determine the precise area of the Atlantic where Ryan would most likely be found.

“We have computer programs that utilize a wide range of environmental data,” Fox says. “Usually they are pretty accurate.”

This time they were not. But the inaccuracy was not the computer’s fault. The crew aboard the Hangin’ Loose underestimated the time Ryan had been overboard.

The Coast Guard was told that Ryan had only been missing for approximately ten minutes, when, in reality, he had been treading water for nearly an hour.

“We have to believe the information the boat crews give us,” Fox says. “I’m confident we would have found him if he was in that area.

We deployed a lot of assets. We always search like it is one of our own family members out there.”

| |Back aboard the Hangin’ Loose, Greg Ryan dons a PFD before a fishing trip. Photo: Andy Snyder|

Left Alone

More than 17 miles northwest from where the Coast Guard was searching, Ryan was facing a torturous night of survival.

“I spent a lot of the time floating on my back,” he says. “That helped me keep my head out of the water without much effort.”

Each time Ryan crested one of the thousands of waves he endured, he was taunted with the glowing, dome-shaped lights of distant Ocean City, Maryland. Under those lights, less than six miles away, thousands of beachgoers were enjoying a summer Friday night on Ocean City’s streets and boardwalk.

“I started swimming toward the glow from Ocean City,” says Ryan.

| |Illustration: Marcos Chin| After realizing that reaching the shoreline was an impossible goal, Ryan turned and began swimming offshore. He knew he was near the shipping channel and the numerous rusty yellow buoys that mark the center of it. If he could get to one of those, he would at least be able to pull his body from the 72-degree water.

“By morning, I was freezing,” he says. “There was nothing I could do to get out of the cold. If I was lost in the jungle or out in the desert, I could think of a million ways to survive, but out there, there was no way to escape it. No matter what I did, nothing changed.”

As the hours dreadfully inched by with no sign of rescuers, Ryan’s physical and mental condition deteriorated.

Every scissor-kick and arm stroke was harder than the last. He began vomiting from the gallons of seawater he had ingested and his breathing became shallow and labored. Each breath of salt-filled air was harder to gasp than the last.

The inside of his mouth became raw and blistered from the salt water that would sneak in with each breath. Ryan’s T-shirt and shorts began to chafe with the abrasiveness of 20-grit sandpaper.

“My back and chest were raw from my clothes,” he says. “The pain was incredible.”

To make matters worse, Ryan began to hallucinate.

“I always keep a small handheld radio on the boat,” he says. “For some reason I thought I was calling my friends on it and got really mad and frustrated when they didn’t answer.”

With his emotional state waning, things started looking even worse. Ryan was convinced he had seen his final sunset, and would be dead before the sun rose again in the east. Certain there was no hope, he reminisced about his life and said his last goodbyes. He remembered the good times, and realized his regrets.

When he had finished, he stopped fighting and allowed his exhausted 34-year-old body to sink toward the ocean bottom less than 80 feet below. He was ready to go.

“Before I knew it, I was back on the surface, fighting. All I could think about was my 13-year-old daughter and how I’d be letting her down. I kept imagining what she was going through,” he says. “I know how bad it was out on the water, but it had to be much worse back at the dock.”

Faith and Hope

Ryan would continue his fight through the rest of the night and into the morning. As his stomach ballooned with seawater, he learned that he could find a temporary respite from the cold by vomiting. The sudden burst of heated seawater gushing from his stomach would instantly warm his chest. Unfortunately, the relief would only last a moment.

Ryan also became the victim of numerous painful fish bites. With little energy remaining, he was helpless as hungry fish attacked any piece of exposed skin. He was covered with dozens of bloody gashes.

“I think they were bluefish – they really hurt,” he says. “Luckily, where I was there are not many sharks, but they were the least of my concerns.”

In between the spouts of vomiting and the fish attacks, Ryan was able to relax his arms by resting them one at a time on a short two-by-four that floated within reach. The debris wasn’t large enough to float his entire body, but it provided just enough buoyancy to rest his failing limbs.

It helped him get through the night.

With the first rays of the morning sun, Ryan knew his long night had ended. As the warmth grew and the sun climbed higher and higher into the morning sky, so did the likelihood of a passing vessel spotting the few square inches of Ryan’s face bobbing above the waves.

“The sun felt great . . . for about an hour,” Ryan said. “After that it started to cook me. I spent the entire night freezing, and all morning burning.”

With higher hopes of a rescue, Ryan clung to life for a few more agonizing hours.

Finally, after 13 hours, the implausible happened.

“I was laying on my back, with my ears under water when I heard the sound of a boat,” Ryan says. “I looked back and saw it coming toward me.” He used his final reserves of energy to wave and yell.

The passing vessel spotted him at 10:30 a.m. The boat came within 25 feet before Gary Williams, its operator, saw Ryan’s exhausted face barely protruding from the water.

“As soon as I knew they saw me,” Ryan says, “I lost every bit of energy I had left. I couldn’t swim any more.”

Williams and his wife, Candace, who had just purchased the new Grady-White the previous day, were headed down the coast to deliver the boat to their home in Virginia.

Williams had no idea the first catch he would drag through the transom door would be a nearly dead man who’s life he had just saved.

Beating the Odds

“From what our survivability models show, he shouldn’t be alive,” Fox says. “Everybody was stunned and ecstatic when we heard they found him alive. Somebody up there must have big plans for Greg Ryan.”

When Ryan finally reached the safety of the emergency room, doctors found that their exhausted patient had gained 40 pounds from ingested seawater.

After fully assessing his condition, Ryan’s doctors said he could not have spent much more time in the water. In fact, Ryan said he had begun to black out just minutes before Williams spotted him.

“There’s a period in there, I can’t remember,” he says. “I do remember suddenly waking up, gagging on seawater. Whether I was out for ten minutes or ten seconds, I don’t know. But I woke up and kept fighting.”

| AN OUNCE OF PREVENTION A snowballing series of critical safety oversights nearly ended Greg Ryan’s life. Here’s what you can do to prevent a similar terrifying accident:* The instant a person falls into the water shout, “Man overboard,” as loudly and clearly as possible. Assign a crew member to watch the person in the water. Then throw several flotation devices into the water. That way the captain will have a trail of objects pointing to the spot where the victim fell overboard.* Make sure the crew and passengers understand emergency procedures. This includes proper use of the electronics. * To practice finding an overboard victim, throw an anchor ball into fairly rough seas and try to locate it. You will quickly learn that unless a constant eye is kept on the ball, it will be nearly impossible to find. * Never go anywhere near the water without a life jacket. It will keep you afloat if you go overboard and provide added visiblity so that rescuers can spot you. * Purchase an electronic device, such as an EPIRB or a personal locator beacon (PLB), like the AquaFix 406 GPS I/O from ACR Electronics. – A. S. |